For the late eighteenth-century, portraits, especially of men and women of accomplishment, was more than a representation of a sitter’s appearance. As William Hazlitt put it, they also expressed of ‘the essence of the sitter, reflect[ing] his thoughts and feelings, the capturing on canvas of subjectivity’. Typically, for composers, this meant not only some sign of their art – a score or a musical instrument – but also characteristic physical features, among them facial expressions that are absorbed or distracted. Thomas Hardy’s 1792 portrait of Haydn shows the composer holding a bound score, his eyes slightly averted from the viewer’s gaze, as if lost in thought; Joseph Duplessis’s 1775 portrait of Gluck shows him at a keyboard, his eyes raised heavenward, toward some higher inspiration.

Thomas Hardy, Joseph Haydn, 1792 (London, Royal College of Music) // Joseph Duplessis, Christoph Willibald Gluck, 1775 (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum)]

Mozart portraits, however, are generally prosaic, with little sense that genius transcends the mundane. Possibly such a portrayal was considered inappropriate for a composer still in his teens or twenties. Or possibly, in spite of being considered by many the greatest composer of his age, Mozart had in some way not yet attained the status of a Haydn or a Gluck. It may even be that most Mozart portraits are prosaic because, by all accounts, Mozart was himself prosaic in appearance: his head was disproportionately large, his hands small, his complexion pale, and he is said to have had a large nose and bulging eyes, as well as pockmarks left over from a childhood bout with smallpox.

Even beyond the character that portraits of Mozart seem to depict, there are also problems of attribution: although several dozen portraits purporting to be of Mozart survive from his lifetime, barely a dozen can be authenticated and even among those that are unquestionably of Mozart, there are sometimes questions concerning their dates of execution or artists. The portraits presented here not only span much of Mozart’s lifetime but also epitomise many of the issues involved in the study of Mozart portraiture.

Carmontelle / Delafosse, Leopold Mozart and his two children 1763-64

Giambettino Cignaroli / Saverio dalla Rosa, Portrait of Mozart, 1770

Pietro Fabris, Concert at the Home of Lord Fortrose, 1770 or 1771

Martin Knoller, Portrait of Mozart c.1773

Della Croce (attr.), The Mozart Family, 1779-1780

Doris Stock, Wolfgang Mozart, Silver-point etching, Dresden 1789

Carmontelle / Delafosse, Leopold Mozart and his two children 1763-64

Carmontelle / Delafosse, Leopold Mozart and his two children 1763-64

Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle, Leopold Mozart and his two children, watercolour, executed at Paris, fall 1763, and engraving, executed at Paris, winter 1764. Copies (Carmontelle): Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Inv. Nr. D. 4496; York, Castle Howard.

In late 1763 or early 1764, the French artist Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle produced several versions, in watercolour or pastel, of a portrait showing Mozart, his father, and his sister, Nannerl, performing. In April 1764 it was engraved, according to Leopold Mozart, by Christian von Mechel: 'M. de Mechel, an engraver in copper, is working hand over fist engraving our portrait, which M. Carmontelle (an amateur) painted very well. Wolfgang plays at a keyboard, I stand behind his chair and play violin, and Nannerl leans on the harpsichord with one hand; in the other she holds a piece of music, as if she were singing.' The engraving, in fact signed by Jean Baptiste Delafosse, was sold both separately and together with the printed editions of Mozart’s sonatas K6-9, in a slightly later English engraving with K10-15, and in Holland with K26-31.

The most widely-circulated image of Mozart at the time, the Delafosse engraving was generally available throughout France, England, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium and Holland until 1778.

This portrait can also be found as an Objects entity

Giambettino Cignaroli / Saverio dalla Rosa, Portrait of Mozart, 1770

Giambettino Cignaroli / Saverio dalla Rosa, Portrait of Mozart, 1770

Giambettino Cignaroli or Saverio dalla Rosa (or possibly both in collaboration), Portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, oil on canvas executed at Verona on 6-7 January 1770, possibly with later additions. Source: privately owned.

The origin and execution of this portrait—commissioned by Pietro Lugiati—is partly described by Leopold Mozart in a letter to his wife, written at Verona on 7 January 1770. It is also mentioned in a review dated 9 January of Mozart’s Verona concert of 5 January, published in the Gazzetta di Mantova for 12 January: ‘. . . on this and other occasions, subject to the most arduous trials, he overcame them all with an inexpressible skill, and thus to universal admiration, especially among music lovers; among them were the Signori Lugiati who, after enjoying and allowing others to enjoy yet finer proofs of this youth’s ability, in the end wished to have him painted from life for a lasting memorial.' Lugiati describes the importance of the picture to him in a letter to Mozart's mother dated 22 April of that year:

- Since the beginning of the present year this our city has been admiring the most highly prized person of Signor Amadeo Volfango Mozart, your son, who may be said to be a miracle of nature in music, since Art could not so soon have performed her mission through him, were it not that she had taken his tender age into account.

- I was certainly among his admirers, although, however much pleasure I have always taken in music and much as I have heard of it on my travels, I cannot hope to be an infallible judge of it; but I have certainly not been mistaken in the case of so amazing a boy, and I have conceived such a regard for him that I had him painted from life. . . This charming likeness of him is my solace, and serves moreover as incitement to return to his music now and again. . .

This portrait can also be found as an Objects entity

Pietro Fabris, Concert at the Home of Lord Fortrose, 1770 or 1771

Pietro Fabris, Concert at the Home of Lord Fortrose, 1770 or 1771

Pietro Fabris, Interieur a Naples. / Lord Seaforth / Sir Hamilton / Pugnani Virtuose / 1770 (Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

According to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, this painting represents a concert at the Neapolitan home of William Mackenzie, Lord Fortrose, who stands in the centre of the picture with his back to the viewer. William Hamilton is portrayed on the left; the violinist is Gaetano Pugnani and the artist appears in the lower left-hand corner. The two keyboard players are said to be Mozart and his father. A notation on the back of the picture reads: ‘Interieur a Naples. / Lord Seaforth [William Mackenzie, Lord Fortrose] / Sir Hamilton / Pugnani Virtuose / 1770.’ The painting within the painting, however, is dated ‘P. Fabris p. 1771’, presumably by the artist himself. Mozart and his father met Pugnani in Turin in January 1771; there is no evidence that they met him earlier, in Naples in 1770, and the painting —even if it does represent Mozart and his father — may have been executed after their stay at Naples.

This portrait can also be found as an Objects entity

Martin Knoller, Portrait of Mozart c.1773

Martin Knoller, Portrait of Mozart c.1773

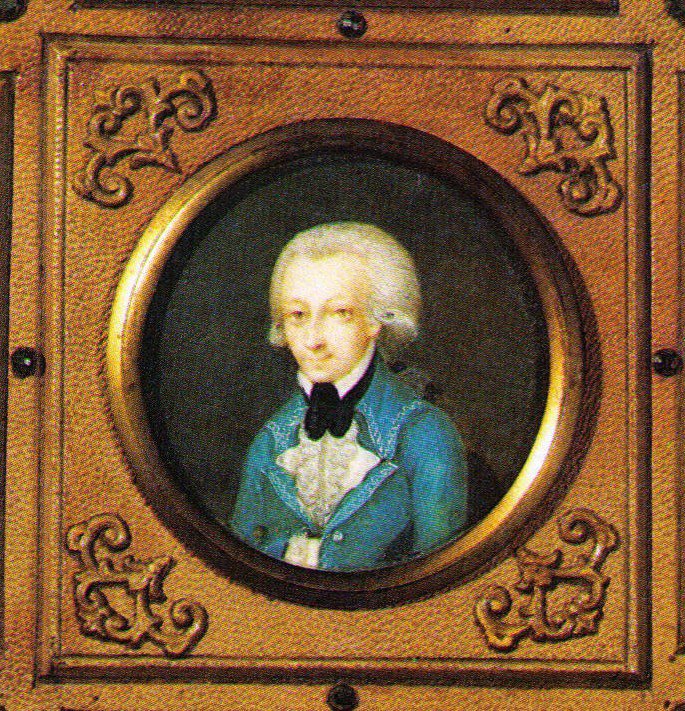

Attr. Martin Knoller, ?Mozart, unsigned miniature on ivory, possibly c1773. Location: Salzburg, Mozart-Museums

The dating of this portrait to c1773 derives from a letter of 2 July 1819 (MBA, iv.455-457) in which Nannerl Mozart describes the commissioning of a portrait from Barbara Krafft, among the models for which she offered an image of Wolfgang done when he was 16: Deutsch (Mozart und seine Welt in zeitgeössischen Bildern, 298), suggests that this image and the Knoller-attributed miniature may be identical. An 1862 catalogue of the Mozarteum archive, however, describes the miniature as dating from 1769 (Moyes, Systematischer). In a letter of 17 February 1770, Leopold responds to a question of Maria Anna’s that suggests Knoller may have been known to the Mozarts even before the first trip to Italy (beginning December 1769). If so, and considering that Leopold and Wolfgang met Knoller during their stays in Milan in 1770 and 1773, the miniature, if authentic and correctly attributed, could date from about this time.

This portrait can also be found as an Objects entity

Della Croce (attr.), The Mozart Family, 1779-1780

Della Croce (attr.), The Mozart Family, 1779-1780

Della Croce (attr.), The Mozart Family, 1779-1780 (Salzburg, Mozart Museums)

The family portrait attributed to Johann Nepomuk della Croce was executed in late 1780 and early 1781. It is mentioned several times in the family letters. On 13 November 1780 Mozart, then in Munich for the premiere of his opera Idomeneo K366, wrote to his father: ‘[What’s happening] with the family portrait? – [how does it] look? – has [the portrait of my] sister been started?’. Leopold answered on 20 November: ‘You ask how the family portrait is coming along? – there’s still no progress. The reason is, I haven’t had time for a sitting and neither has the artist. And I won’t let your sister out of the house.’ There was still no progress on 15 December, as Leopold told Wolfgang, in part because Nannerl, he said, was still ill – which also explains his comment that he wouldn’t let her out of the house. Nannerl was better by the end of December and reported to her brother on 30 December that she would sit for the artist the next day; by 8 January she had been to a second sitting. There are no further mentions of the portrait in the family correspondence during Mozart’s lifetime. These letters make it clear that Mozart only sat for the portrait well before it was finished, and before he left Salzburg for Munich on 5 November 1780. He cannot have sat for the artist afterwards as he did not return to Salzburg in the spring of 1781 but instead travelled to Vienna, where he largely remained until his death in 1791. It is unlikely the portrait remained unfinished by the summer of 1783, the only time Mozart returned to Salzburg in the following decade.

The portrait shows Mozart and his sister performing a four-hand keyboard work – to that time Mozart had composed two four-hand sonatas, K381 (1772) and K358 (1773-1774); Leopold Mozart holding a violin, the instrument for which he was best known; and it includes a portrait within a portrait, of Mozart’s mother, who had died in Paris in 1778.

This portrait can also be found as an Objects entity.

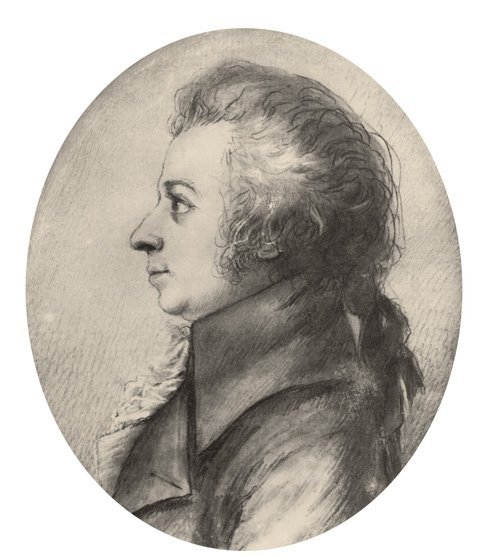

Doris Stock, Wolfgang Mozart, Silver-point etching, Dresden 1789

Doris Stock, Wolfgang Mozart, Silver-point etching, Dresden 1789

Dresden 1789: silverpoint etching by Doris Stock (Stiftung Mozarteum, Salzburg)

While widely accepted as an authentic portrait of Mozart[1], a silverpoint etching by Doris Stock, said to have been executed during Mozart’s visit to Dresden in 1789, is nevertheless problematic. Otto Erich Deutsch states as fact that ‘On 16 or 17 April [1789] Mozart visited the consistorial councillor Christian Gottfried Körner, whose sister-in-law Doris Stock did a drawing of Mozart.’[2] Yet there is no reference in Mozart’s letters to Körner or Stock, and the earliest accounts of his acquaintance with them date from almost a century later. Friedrich Förster reported in 1879 that Mozart visited the Körner household at least once during his visit to Dresden and played selections from Don Giovanni for them[3] while a few years earlier, in 1871, Gustav Parthey reported from Doris Stock’s memoirs:

- Mozart himself, during his short stay in Dresden, was an almost daily visitor to the Körner’s house. For the charming and witty Doris he was all aflame, and with his south German vivacity he paid her the naivest compliments. He generally came shortly before dinner and, after he had poured out a stream of gallant phrases, he sat down to improvise at the pianoforte. In the next room the table was meanwhile being set and the soup dished up, and the servant announced that dinner was served. But who could tear himself away when Mozart was improvising! The soup was allowed to grow cold and the roast to burn, simply so that we could continue to listen to the magic sounds which the master, completely absorbed in what he was doing and unaware of the rest of the world, conjured from the instrument. Yet one finally grows tired even of the highest pleasures when the stomach makes known its demands. After the soup had grown cold a few times while Mozart played, he was briefly taken to task. “Mozart”, said Doris, gently laying her snow-white arm on his shoulder, “Mozart, we are going in to dine; do you want to eat with us?” – “Your servant, Mademoiselle, I shall be with you in a moment.” But it was precisely Mozart who never did come; he played on undisturbed. Thus we often had the rarest Mozartian musical accompaniment to our meal, Doris concluded her narrative, and when we rose from table we found him still sitting at the keyboard.[4]

There is no corroborating evidence for either account, and Doris Stock’s self-serving version singularly fails to mention a portrait. Whether Mozart was an almost daily visitor at Körner’s is also open to question: the composer arrived at Dresden about 6 o’clock on the evening of 12 April and went more or less directly to visit the singer Josepha Duschek at the home of the war secretary Johann Leopold Neumann; on 13 April he gave a private concert at the ‘Hotel de Pologne’ where he was lodging; he played at court on the evening of the 14th and went to the opera (Domenico Cimarosa’s Le trame deluse) on the 15th; and he departed on the 18th. None of this rules out the possibility that Mozart and the Körner’s were close or that he visited them during the day: dinner at the time was a mid-day meal and most of Mozart’s engagements were in the evening. But it does suggest that Deutsch’s dating of the portrait specifically to 16 or 17 April is not based on any positive evidence but on the fact that these are the only two days during Mozart’s stay in Dresden when his whereabouts cannot to some extent be accounted for.

A slip of paper formerly attached to the back of the picture, but now lost, complicates matters. When it was removed from the etching sometime in the early twentieth century, it was shorn of its left, and part of its right, sides; as a result, the facsimile edition ‘reconstructs’ what is believed to be the original text. Yet it was not necessary to guess what the missing text might have been: the entire slip of paper had been transcribed as early as 1899, in Emil Vogel’s article on Mozart portraits, before some of the text was lost.[5]

| Zettel as it now survives | Reconstructed text by G. Geffray (2005) | Original text after E. Vogel (1899) |

| [Anna Maria Körner, after 1832?:] | ||

| Erhält | Erhält | |

| [?...] Förster | Förster | |

| [Friedrich Christoph Förster, 1859:] | ||

| von Doris Stock | ... von Doris Stock | Dieses von Doris Stock |

| resden 178 | … [D]resden 178[9] | In Dresden 1787 |

| eben gezeichn | … [?von L]eben gezeichn[et…] | Nach dem Leben gezeichnete |

| niβ Mozar | … [?Bild]niβ Mozar[ts] | Bildniβ Mozarts |

| mir von G. Koh | … mir von G. Koh[?rner] | wurde mir von Th. Körners |

| ter geschenkt und | … [?wei]ter geschenkt und . . . | Mutter geschenkt und von |

| ir Carl Eckert | … [?D]ir Carl Eckert […] | mir Carl Eckert. |

| 22/5 F. Förste | … 22/5 F. Förste[r…] | Berlin, 23/5 F. Förster |

| 1859 |

Much of the attempted reconstruction is accurate enough although at least two details of the original text, different from the reconstructed text, are significant. First, the slip was not written in the early nineteenth century, close to the execution of the portrait, as Geffray claims[6], but at third-hand, in 1859, some seventy years after the event it purports to document — and, as it happens, a year after an engraving based of the portrait, said to be of Mozart, had already been published. What is more, Förster cannot necessarily be considered a reliable witness; he was later exposed as having falsified the historical record in his history of the life and poetry of Theodor Körner[7]. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the original slip of paper states that the etching was executed in 1787, not 1789. Yet Mozart wasn’t in Dresden in 1787 and Stock, as far as we know, wasn’t in Vienna or Prague[8].

There is, accordingly, no unequivocal contemporaneous evidence that Mozart, Körner and Stock met in Dresden in 1789; the surviving prose accounts of their alleged meetings say nothing about a portrait; the date for its presumed execution is fixed only by our lack of knowledge of Mozart’s whereabouts on two days during his stay in Dresden; and the best information we have, the slip of paper formerly attached to the etching, is third-hand and contradicts the presumed date of 1789 for the etching’s execution, suggesting instead a date, 1787, that is biographically impossible. None of this is to say that the Stock is not Mozart. It may well be. But insofar as the evidence is concerned, there is little reason to believe it must be what it is purported to be.

This portrait can also be found as an Objects entity.

[1] See Mozart-Bilder, Bilder Mozarts. Ein Porträt zwischen Wunsch und Wirklichkeit, ed. Christoph Großpietsch (Salzburg: Verlag Anton Pustet, 2013), 74, and the facsimile edition, Geneviève Geffray, ed., Das letzte Porträt Wolfgang Amadé Mozarts. Die Silberstiftzeichnung von Doris Stock (Salzburg, 2005).

[2] Otto Erich Deutsch, Mozart. A Documentary Biography (London, 1966), 340. The same claim is made by Geffray, Das letzte Porträt Wolfgang Amadé Mozarts, 6, 14 and 20.

[3] Friedrich Förster, ed., Theodor Körners Werke. Vollständigste Ausgabe mit mehreren bisher ungedruckten Gedichten und Briefen. Nebst einer Biographid des Dichters (Berlin, 1879), i.40.

[4] Deutsch, Mozart. A Documentary Biography, 568-9.

[5] For the Zettel as it now survives and Geffray’s transcription, see Das letzte Porträt Wolfgang Amadé Mozarts, 4 and 8; for the original text, see Emil Vogel, ‘Mozart-Portraits’, Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters 6 (1899), 29.

[6] Geffray, Das letzte Porträt Wolfgang Amadé Mozarts, 8, 16 and 22.

[7] John Stone and Louise Williams, ‘Portraits of Mozart. Revising the Iconography’, Apollo: The International Magazine of the Arts 34/357 (November 1991), 314.

[8] Christoph Grosspietsch, ‘Die späten Mozart-Bildnisse (um 1789) von Posch, Stock und Lange’, Mozart-Jahrbuch 2009/2010, 49, dismisses the contradiction out of hand, suggesting that the date 1787 on the Zettel may simply be an error, either of the now-lost original or Vogel’s transcriptions of it.