This is a lengthy document. For readers who prefer to have a paper version, you can download the PDF version of this Biography by clicking on the link below:

Mozart BiographyChild prodigy, composer, virtuoso performer.

According to a possibly apocryphal story, when the conductor Otto Klemperer was asked to list his favourite composers, Mozart was not among them. On being taxed with his, Klemperer is said to have replied, 'Oh, I thought you meant the others'. This anecdote illustrates how Mozart is often regarded, almost as a matter of course: as a pre-eminent (some would say 'the' pre-eminent) composer of operas, concertos, symphonies and chamber music.[1] His life and works can conveniently be divided into three distinct periods: 1756-1773 when, as a child prodigy, he toured much of Western Europe and composed his first works; 1773-1780, when he was largely based in Salzburg in the employ of the Salzburg court (with a significant interruption from September 1777 to January 1779, when he quit service in search of a position at either Mannheim or Paris); and 1781-1791, when he was permanently resident in Vienna and during which time he composed the works for which he is best remembered. Most Mozart biographers see in this three-fold division a pattern that, even if its dates do not exactly correspond with the traditional, Rousseauian model of a creative life - apprenticeship (which for Mozart is said to extend from 1763 to the late 1770s), maturity (the late 1770s to about 1788), and decline (about 1788-1791) - is nevertheless more or less consistent with how other composers' lives, including Palestrina, Beethoven and Rossini, are usually represented. The one significant difference, perhaps, is that Mozart's alleged decline is 'redeemed' by the composition, in his final year, of two transcendent works: the sacred Requiem and the secular The Magic Flute.

This biographical construction, however, hardly does justice to the life Mozart must have experienced, not least in its music-centricity: more often than not, the facts of Mozart's everyday life, his education, his travels, and the social and cultural constructs and currents of his time, remain unconnected to his music, except in obvious instances such as commissions and works demonstrably composed for special occasions or his early works, usually said to repre4sent his assimilation of local models, wherever he happened to be at their time of composition. Yet the traditional three-part model need not be abandoned, only refined, for each of these distinct periods in his life corresponds fairly closely with a fundamental response, in part through his music, to the places he traveled, the conditions of his employment, and, during the last decade of his life, his navigation of an independent personal life, and partly-independent, partly-court- bound musical career in Vienna.

1756-1773: [Anchor name: toc_item_one] Early tours

1773-1780: [Anchor name: toc_item_two] Mozart and Salzburg

1781-1791: [Anchor name: toc_item_three] Mozart in Vienna

▲[Anchor name: section_one] 1756-1773 : Early Tours

Mozart – his baptismal name was Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus – was born at Salzburg, then an independent archdiocese ruled by a prince-archbishop, on 27 January 1756. He was the seventh and last child of Leopold Mozart (1719–1787) and his wife Maria Anna née Pertl (1720–1778) and only the second, after his sister Maria Anna, known as ‘Nannerl’ (1751–1829), to survive. Leopold, who in 1737 had left his native Augsburg to study at the Salzburg Benedictine University but was expelled for insubordination and for failing to complete his studies, married Maria Anna on 21 November 1747, while employed as a violinist in the Salzburg court music establishment. A composer and theorist as well as an accomplished violinist, he was well-known throughout parts of German-speaking Europe even before Wolfgang’s birth and the publication of his important Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule, also in 1756. His duties at court included not only performing but also teaching violin, arranging for the purchase of music and music instruments, composing and, on a regular, rotating basis, directing the court music.

The Mozart family rented an apartment on the third floor of the house at Getreidegasse 9, which was owned by Johann Lorenz Hagenauer, who ran a thriving spice and grocery business with connections throughout western Europe. The Getreidegasse itself was home to home to nearly twenty percent of Salzburg’s population at the time, including court offices, bakers, goldsmiths, grocers, musicians, hotels and drinking establishments. Almost directly across the street from the Mozarts was the Rathaus or town hall, the central locus for much of the public activity in the city such as concerts, balls and town meetings. From his earliest years, then, Mozart was surrounded by the hustle and bustle of a small but prosperous metropolitan centre that, as the leading independent church state north of the Alps, offered considerable scope for social and cultural activity even if, size-wise, it paled by comparison with the major cities he was to visit later.

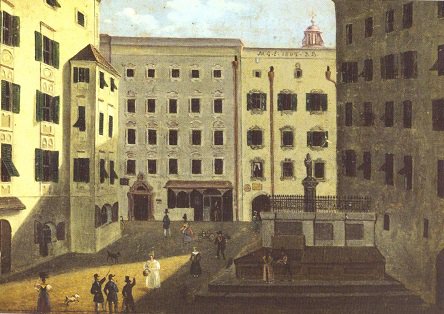

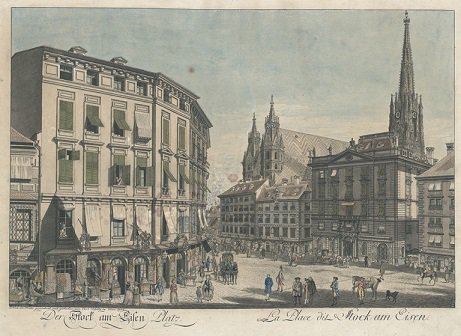

Anon, Löchlplatz (now the Hagenauerplatz) directly across from Mozart’s birthplace, Getreidegasse 9. The fountain was removed in 1858 (original: Salzburg Museum)

As far as is known, Leopold was entirely responsible for the education of his children, which included not only music, but also mathematics, reading, writing, literature, languages, dancing and moral and religious training. Mozart’s musical talent was apparent early on. In 1759, Leopold started to compile a music notebook with lessons, at first mainly short minuets and trios, that he used to teach Mozart’s older sister Nannerl. By the time he was four, Mozart had learned several pieces in the book: Leopold wrote below a scherzo by Wagenseil that ‘Wolfgangerl learned this piece between 9 and 9.30 on the evening of 24 January 1761, 3 days before his fifth birthday‘ and below one of the first works entered in it, an anonymous minuet and trio, ‘Wolfgangerl learned this minuet and trio in a half hour at half past 10 on the evening of 26 January 1761, a day before his 5th birthday’. Shortly afterwards it became ‘home’ to his earliest compositions, including the andante K1a and the allegros K1b and K1c which, according to Leopold, Mozart composed ‘in the first three months after his 5th birthday.’

Although there is no record of public keyboard performances by Mozart or his sister in Salzburg at this time, by the end of 1761 Leopold had decided that the children were sufficiently accomplished to tour both Munich and Vienna. He took them to the Bavarian capital in January 1762 (there is no documentation for this trip other than a later reminiscence of Nannerl Mozart’s), where they played for Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria, and in late September to Vienna, where they appeared twice before Maria Theresa and her consort, Francis I, as well as at the homes of various nobles and ambassadors. On 16 October Leopold wrote to his Salzburg landlord, Lorenz Hagenauer: '. . . we have already attended a concert at Count Collalto’s, also Countess Sinzendorf introduced us to Count Wilczek and on the 11th to His Excellency the imperial vice-chancellor Count Colloredo, where we had the privilege of seeing and speaking to the leading ministers and ladies of the imperial court. I received orders to go to Schönbrunn on the 12th. . . We were received with such extraordinary kindness by their majesties that if ever I tell them about it, people will say I have made it all up. Suffice it to say that Wolferl jumped up into the empress’s lap, grabbed her round the neck and kissed her right and proper.'

During their stay in Vienna, the French ambassador, Florent-Louis-Marie, Count of Châtelet-Lomont, extended to them an invitation to perform at Versailles, and this may have been the inspiration for an even grander venture: a tour of Germany, France, Belgium, Holland, England and Switzerland that began in June 1763 and lasted nearly three-and-a-half years. Among the family’s chief destinations was Paris, where the family arrived on 18 November 1763; they had traveled by way of Munich, Augsburg, Ludwigsburg, Mainz, Frankfurt, Coblenz, Aachen and Brussels, giving public concerts, performing privately for local monarchs and nobility, visiting churches and other landmarks, and generally laying the groundwork for the next leg of their journey. In Paris they played before Louis XV on New Year’s day 1764, and they gave public concerts on 10 March and 9 April at the private theatre of a M. Félix in the rue et porte Saint-Honoré. Their most important patron was the German expatriate journalist and diplomat Friedrich Melchior Grimm, who shortly after the family’s arrival in Paris wrote about the children in his widely-distributed Correspondance Littéraire: “True prodigies are sufficiently rare to be worth speaking of when you have had occasion to see one. A Kapellmeister of Salzburg, Mozart by name, has just arrived here with two children who cut the prettiest figure in the world. His daughter, eleven years of age, plays the harpsichord in the most brilliant manner; she performs the longest and most difficult pieces with an astonishing precision. Her brother, who will be seven years old next February, is such an extraordinary phenomenon that one is hard put to believe what one sees with one's eyes and hears with one's ears. I cannot be sure that this child will not turn my head if I go on hearing him often; he makes me realize that it is difficult to guard against madness on seeing prodigies. I am no longer surprised that Saint Paul should have lost his head after his strange vision.”

In early 1764 Leopold arranged to have four sonatas for keyboard and violin by Wolfgang published with dedications to Princess Victoire of France, Louise XV’s second daughter (K6-7), and to Adrienne-Catherine, Comtesse de Tessé, lady-in-waiting to the Dauphine, Princess Maria Josepha of Saxony (K8-9). As Leopold described it in a letter of 3 December 1764, he wanted the public to know they were the work of a prodigy and accordingly accepted some trivial mistakes in the sonatas: ‘I regret that a few mistakes have remained in the engraving, even after the corrections were made. . . That is the reason why especially in opus II in the last trio you will find three consecutive fifths in the violin part, which my young gentleman perpetrated and which, although I corrected them, old Madame Vendôme left in. On the other hand, they are proof that our little Wolfgang composed them himself, which, perhaps quite naturally, not everyone will not believe.’ He also arranged for a family portrait to be executed by the painter Louis Carrogis (known as Carmontelle), showing Wolfgang at the keyboard, Leopold standing behind him playing the violin, and Nannerl singing. At least four copies of the portrait were made but more importantly, it was engraved as a ‘souvenir’ of the family and sold together with Wolfgang’s earliest sonatas. Widely distributed – not just in Paris but also in London and throughout western Europe as late as 1778 – it was the dominant public image of Mozart at least until his move to Vienna in early 1781.

It was not Leopold’s original intention to travel from Paris to London. On 28 May 1764 he wrote to Hagenauer, ‘When I left Salzburg, I was only half resolved to go to England: but as everyone, even in Paris, urged us to go to London, I made up my mind to do so; and now, with God’s help, we are here.’ Within days of their arrival they played for George III, in June they gave a concert for their own benefit at the Great Room in Spring Garden, and later that month Wolfgang performed ‘several fine select Pieces of his own Composition on the Harpsichord and on the Organ’ at Ranelagh Gardens during breaks in a performance of Handel’s Acis and Galatea. Further benefit concerts (possibly including Wolfgang’s earliest symphonies, K16 and K19) were given the next season, on 21 February and 13 May 1765. After nearly fifteen successful months in London, including the publication of keyboard and violin sonatas dedicated to Queen Charlotte (K10-15), the family left in July 1765. It was a visit that left a lasting impression on both the Mozarts and eighteenth-century Londoners – on the Mozarts because they collected engravings of the London sites they had visited, and for Londoners because of the novelty of some of Wolfgang’s performances at the time; as late as 1784 the European Magazine and London Review recalled that ‘the first instance of two persons performing on one instrument in this kingdom, was exhibited in the year 1765, by little Mozart and his sister.’

From London the family intended to return to Paris, but as Leopold Mozart wrote in a letter of 19 September 1765: ‘The Dutch envoy in London repeatedly urged us to visit the Prince of Orange in The Hague but I let this go in one ear and out the other. . . On the day of our departure the Dutch envoy drove to our lodgings and discovered that we had gone to Canterbury for the races, after which we would be leaving England. He was with us in a trice and begged me to go to The Hague, saying that the Princess of Weilburg – the sister of the Prince of Orange – was extraordinarily anxious to see this child, about whom she had heard and read so much. . .’ The Mozarts played for Caroline, Princess of Nassau-Weilburg (to whom Mozart later dedicated the sonatas K26-31), on 12 and 19 September and gave at least six public concerts, at The Hague, Amsterdam and Utrecht, between September 1765 and April 1766. In March they attended the installation of Wilhelm V as Prince of Orange, for which Mozart composed the Galimathias musicum K32 (his other works from this time include the symphony K22, the aria Conservati fedele K23, and two sets of variations for keyboard K24 and K25, on the song ‘Willem van Nassu’).

The family returned to Paris on 10 May 1766, staying for two months before setting out on the last leg of their journey, traveling to Salzburg circuitously by way of Dijon, Lyons, Lausanne, Zurich, Donaueschingen, Dillingen, Augsburg and Munich. They arrived home on 29 November 1766, an event noted in the diary of Beda Hübner, a family friend and librarian at the monastery of St. Peter’s in Salzburg: 'I cannot forbear to remark here also that today the world-famous Herr Leopold Mozart, deputy Kapellmeister here, with his wife and two children, a boy aged ten and his little daughter of 13, have arrived to the solace and joy of the whole town. . . There is a strong rumour that the Mozart family will again not long remain here, but will soon visit the whole of Scandinavia and the whole of Russia, and perhaps even travel to China, which would be a far greater journey and bigger undertaking still: de facto, I believe it to be certain that nobody is more celebrated in Europe than Herr Mozart and his two children.'

The Mozarts remained in Salzburg for barely nine months, during which time Wolfgang wrote the Latin comedy Apollo et Hyacinthus, the first part of the oratorio Die Schuldigkeit des ersten und fürnehmsten Gebots and the Grabmusik K42. They set out – not for Scandinavia, Russia or China but for Vienna - in September 1767. Presumably Leopold timed this visit to coincide with the festivities planned for the marriage of the sixteen-year-old Archduchess Josepha to King Ferdinand IV of Naples. Josepha, however, contracted smallpox and died the day after the wedding was to have taken place. While the court was in mourning, and in order to protect his children from the outbreak, Leopold took his family first to Brünn (now Brno) and the Olmütz (now Olomouc), where both Nannerl and Wolfgang nevertheless had mild attacks.

Shortly after their return to Vienna in January 1768, Leopold conceived the idea of securing for Wolfgang an opera commission, La finta semplice. But court intrigues conspired against its performance and after several months of frustration and mistreatment at the hands of the court musicians – so Leopold claimed – he wrote the Emperor a petition, asking for redress: ‘[Were these intrigues] to be the reward that my son was to be offered for the great labour of writing an opera and for the waste of time and the expenses we have incurred? And ultimately, what of my son’s honor and fame now that I no longer dare insist on a performance of the opera, since I have been given to understand plainly enough that no effort will be spared in performing it as wretchedly as possible; and since, futhermore, they are claiming now that the work is unsingable, now that it is untheatrical, now that it does not fit the words, now that he is incapable of writing such music (and all manner of foolish and self-contradictory nonsense, all of which would vanish like smoke to the shame of our envious and perfidious slanderers if, as I most urgently and humbly entreat Your Majesty for my honor’s sake, the musical powers of my child were to be properly examined, so that everyone would then be convinced that the only aim of these people is to stamp on and destroy the happiness of an innocent creature to whom God has granted an extraordinary talent and whom other nations have admired and encouraged, and to do this, moreover, in the capital of his German fatherland.’ As a result of Leopold’s petition, Joseph II ordered an investigation but nothing came of it and La finta semplice was not performed. Presumably as compensation, Wolfgang was asked to compose a trumpet concerto (K47c, lost), an offertory (K47b, lost) and a mass (K139) that were given on 7 December at the dedication of the orphanage church Mariae Geburt in the Renweg. During his time in Vienna Mozart also composed two symphonies (K45 and K48), the German singspiel Bastien und Bastienne (K50) and in December he published two songs, An die Freude and Daphne, deine Rosenwangen (K52 and K53), in the Neue Sammlung zum Vergnügen und Unterricht, a periodical for children.

The Mozarts returned to Salzburg in January 1769 where La finta semplice may have been given to celebrate the nameday of Archbishop Schrattenbach in May and Wolfgang apparently composed three substantial orchestral serenades (K63, K99 and K100) – documents show that two such works were performed in August to mark the end-of-year celebrations of the logicians and physicians at the Salzburg Benedictine University – as well as the so-called ‘Dominicus’ mass (K66), which was performed at St Peter’s in recognition of the first mass celebrated by Lorenz Hagenauer’s son Kajetan Rupert, who had taken the name Father Dominicus. Presumably in recognition of his reputation as a composer and performer, in November Mozart was appointed to the Salzburg court music as third violinist on an unpaid basis, with the promise of a paid position on his return from an upcoming trip to Italy that was subsidized in part by the Archbishop.

In December, father and son set out for Italy – where they would travel two more times before the end of 1773 – traveling by way of Innsbruck and Rovereto to Verona, where they arrived on 27 December and where Mozart gave a public concert on 5 January that was reviewed in the Gazzetta di Mantova on 12 January: 'This city cannot do otherwise than declare the amazing prowess in music possessed, at an age still under 13 years, by the little German boy Sig. Amadeo Wolfango Motzart, a native of Salzburg and son of the present maestro di cappella to His Highness the Prince-Archbishop of that city. On this and other occasions, subject to the most arduous trials, he overcame them all with an inexpressible skill, and thus to universal admiration, especially among the music-lovers; among them were the Signori Lugiati, who, after enjoying and allowing others to enjoy yet finer proofs of this youth's ability, in the end wished to have him painted from life for a lasting memorial.'

The reference to Lugiati and the portrait he commissioned of Mozart is another example, after the Carmontelle family portrait, of the importance in the eighteenth-century of visual images as both keepsakes and inspiration, a point Lugiati himself made in a letter of 22 April 1770 to Mozart’s mother, Anna Maria: ‘Since the beginning of the present year this our city has been admiring the most highly prized person of Signor Amadeo Volfango Mozart, your son, who may be said to be a miracle of nature in music, since Art could not so soon have performed her mission through him, were it not that she had taken his tender age into account. I have conceived such a regard for him that I had him painted from life . . . This charming likeness of him is my solace, and serves moreover as incitement to return to his music now and again, so far as my public and private occupation will permit.’

Giambettino Cignaroli, Portrait of Mozart, Verona 1770 (original: privately owned)

After a brief stop in Mantua, where he gave a concert on 16 January that was described by the local newspaper as ‘a brilliant success’, Mozart and his father arrived at Milan on 23 January. There they were patronized by Count Karl Joseph Firmian, the Austrian minister plenipontentiary, and it was presumably as a result of his performances for Firmian, and in particular a grand concert on 12 March for which he composed several arias (possibly K77 and versions of K71 and K83), that Wolfgang was commissioned to write an opera for the 1770-71 Milan season, Mitridate, re di Ponto.

From Milan the Mozarts traveled via Lodi, Piacenza, Parma, Modena and Bologna to Florence, where they were received by Leopold, Grand Duke of Tuscany, met the famous contrapuntist Eugenio Marquis de Ligniville, and renewed their acquaintance with the famous castrato Giovanni Manzuoli, whom they had met in London. Mozart also struck up a friendship with the young English violin prodigy Thomas Linley, a pupil of Pietro Nardini, who according to Leopold’s letter to his wife of 21 April 1770, ‘plays most beautifully and who is the same age and the same size as Wolfgang. . . The two boys performed one after the other throughout the whole evening, constantly embracing each other. On the following day the little Englishman, a most charming boy, had his violin brought to our rooms and played the whole afternoon, not like boys, but like men! Little Tommaso accompanied us home and wept bitter tears, because we were leaving the following day.’

From Florence Mozart and his father traveled to Rome, where they arrived on 10 April, in time for Holy Week. Mozart famously made a clandestine copy of Allegri’s Miserere and may have composed two or three symphonies (a reference in Mozart’s letter of 25 April is ambiguous: ‘When I have finished this letter I will finish a symphony which I have begun. . . A[nother] symphony is being copied’) as well as the aria Se ardire, e speranza K82. On 5 July Clemens XIV created Mozart a Knight of the Golden Spur, a personal honour bestowed by the Pope for special services. In the meantime, Wolfgang and Leopold had traveled to Naples where they met William Hamilton and his wife Catherine, attended Niccolò Jommelli’s opera Armida, and visited the local sites: 'On the 13th - St Anthony`s Day - you`d have found us at sea. We took a carriage and drove out to Pozzuoli at 5 in the morning, arriving there before 7 and taking a boat to Baia, where we saw the baths of Nero, the underground grotto of Sybilla Cumana, the Lago d’Averno, Tempio di Venere, Tempio di Diana, il Sepolchro d’Agripina, the Elysian Fields or Campi Elisi, the Dead Sea, where the ferryman was Charon, la Piscina Mirabile and the Cente Camerelle etc., on the return journey many old baths, temples, underground rooms etc., il Monte Nuovo, il Monte Gauro, il Molo di Pozzoli, the Coliseum, the Solfatara, the Astroni, the Gotta del Cane, the Lago di Agnano etc., but above all the Grotto di Pozzuoli and Virgil’s grave.' Most of the summer was spent in Bologna (where with help from the renowned contrapuntist Padre Martini Mozart was admitted to the local Accademia Filarmonica after composing the antiphon Quaerite primum regnum Dei K86) at the summer home of the renowned Field Marshall Giovanni Luca Pallavicini. He returned to Milan in October, and began to work in earnest on Mitridate, re di Ponto, which was premiered at the Regio Ducal Teatro on 26 December; including the ballets, it lasted six hours. Leopold had not been confident that the opera would be a success but it was, running to twenty-two performances.

Pietro Fabris, Vesuvius seen from the grounds of William Hamilton's estate, 1767 (privately owned)

The Mozarts left Milan on 14 January 1771, stopping at Turin, Venice, Padua and Verona before returning to Salzburg at the end of March. All in all the trip was a notable success, garnering not only praise for Wolfgang but also further Milanese commissions, including the serenata Ascanio in Alba for the wedding the following October of Archduke Ferdinand and Princess Maria Beatrice Ricciarda of Modena, and the first carnival opera of 1773, Lucio Silla. Accordingly, Leopold and Wolfgang spent barely five months at home in 1771, during which time Mozart composed the Regina Coeli K108, the litany K109 and the symphony K110. Father and son set out again on 13 August, arriving at Milan on 21 August. Mozart received the libretto for Ascanio at the end of that month, the serenata went into rehearsal on 27 September, and the premiere took place on 17 October. Hasse’s Metastasian opera Ruggiero, also commissioned for the wedding, had its first performance the day before; according to the Florentine Notizie del mondo for 26 October, ‘The opera has not met with success. . . The serenata, however, has met with great applause, both for the text and the music.’ Leopold may have angled for employment at Ferdinand’s court about this time but his application was effectively rejected by Ferdinand’s mother, Maria Theresia, who in a letter of 12 December advised her son against burdening himself with ‘useless people’ who ‘go about the world like beggars’, an ill-conceived and inaccurate slight against the Mozarts.

The third and last Italian journey, for the composition and performance of Lucio Silla, began on 24 October 1772; the opera, premièred on 26 December, had a mixed success, chiefly because of its uneven cast. Although there was little reason to delay their departure from Milan, they did not leave until March; Leopold claimed to be ill but may have applied for a position with Archduke Leopold of Tuscany, to whom he had sent a copy of the opera. Nothing came of this, however, and Wolfgang and his father set out for Salzburg about 4 March, traveling by way of Verona, Ala, Trento, Brixen and Innsbruck, arriving home on 13 March 1773.

Both the western European tour of 1763-66 and the three trips to Italy between late 1769 and 1773 were largely managed through a network of financial and social contacts. For the western European tour, it was the Mozart’s Salzburg landlord Hagenauer who arranged letters of credit and put Leopold in contact with bankers and other merchants who could execute bills of exchange for him. And aside from Munich and Leopold’s native Augsburg, where he already had extensive social contacts, it was word of mouth, newspaper articles and correspondence among the nobility, diplomats and intellectuals that paved the way for the family as they moved from place to place. Shortly after the family’s arrival in London, the French philosopher Claude Adrien Helvetius wrote to Francis, 10th Earl of Huntingdon, ‘Allow me to ask your protection for one of the most singular beings in existence. He is a little German prodigy who has arrived in London the last few days. He plays and composes on the the spot the most difficult and the most agreeable pieces for the harpsichord. He is the most eloquent and the most profound composer in this kind. . . All Paris and the whole French court were enchanted with this little boy.’ Often such high-powered recommendations were unnecessary; Pierre-Michel Hennin, the French resident ambassador in Geneva wrote to Grimm on 20 September 1765 that ‘I was honored to receive from M. Mozart the letter of recommendation you wrote for him. His children’s reputation was already so well-known here that they had no need of recommendations.’

In Italy, by contrast, the Mozarts had a ready-made social network: the southern branches of prominent Salzburgers and their extended families and acquaintances. Shortly before their departure from Salzburg in December 1769, Franz Lactanz von Firmian, Obersthofmeister (the equivalent of Lord Chamberlain) in Salzburg and nephew of the first Archbishop for whom Leopold had worked, Leopold Anton Eleutherius von Firmian, wrote a letter of recommendation for the Mozarts to his cousin Karl Joseph von Firmian, Governor-General of Lombardy. Karl Joseph, in turn, wrote to Bologna, to Count Giovanni Luca Pallavicini-Centurione, a distinguished military man and former Governor-General of Lombardy. The upshot of this chain of recommendations, a chance encounter in Rome with Pallavicini’s cousin Cardinal Lazzaro Opizio Pallavicini, the Vatican secretary of state, was described by Leopold Mozart in a letter to his wife of 14 April 1770:

After arriving here on the 11th, we went to St Peter’s after lunch and then to mass, on the 12th we attended the Functiones and found ourselves very close to the pope while he was serving the poor at table, as we were standing beside him at the top of the table. But our fine clothes, the German language, and my usual freedom in telling my servant to speak to the Swiss Guards in German and make way for us soon helped us through everywhere. They thought Wolfg. was a German gentleman, others even took him for a prince, and our servant let them believe this; I was taken for his tutor. And so we made our way to the cardinals’ table. There it chanced that Wolfg. ended up between the chairs of two cardinals, one of whom was Cardinal Pallavicini.The latter beckoned to Wolfg. and said to him: Would you be good enough to tell me in confidence who you are? Wolfg. told him everything. The cardinal replied with the greatest surprise and said: Oh, so you’re the famous boy about whom so many things have been written? To this, Wolfg. asked: Aren’t you Cardinal Pallavicini? – – The cardinal answered: Yes, I am, why? – – Wolfg. then said to him that we’d got letters for His Eminence and were going to pay him our respects. The cardinal was very pleased by this and said that Wolfg. spoke very good Italian, saying, among other things: ik kann auck ein benig deutsch sprecken etc. etc.

But patrons could also be difficult: some, like Charles Alexandre of Lorraine, Governor of the Austrian Netherlands, made the Mozarts wait more than three weeks without hearing them; Leopold wrote to Hagenauer on 4 November 1763 that ‘Prince Karl has spoken to me himself and has said that he will hear my children in a few days, yet nothing has happened. Yes, it looks as if nothing will come of it, for the Prince spends his time hunting, eating and drinking. . .’. Performers, especially singers, could be difficult as well. The tenor Guglielmo d’Ettore, who sang the title role in Mitridate, insisted that Mozart rewrite his arias multiple times and in the end managed to smuggle one of his trunk arias into the production at the expense of one of Mozart’s. Lucio Silla hardly fared better. Leopold wrote to his wife on 2 January 1773 that its première was nearly ruined by the tenor Bassano Morgnoni: '. . . you need to know that the tenor, whom we’ve had to take faute de mieux, is a church singer from Lodi and had never performed in such a prestigious theatre and had appeared as primo tenore only about twice before in Lodi, and was signed up only about a week before the opening night. He has to gesture angrily at the prima donna in her first aria, but his gesture was so exaggerated that it looked as though he was going to box her ears and knock off her nose with his fist, causing the audience to laugh. Fired by her singing, Sgra De Amicis didn’t immediately understand why the audience was laughing and was badly affected by it, not knowing initially who was being laughed at, so that she didn’t sing well for the whole of the first night, in addition to which she was jealous because the archduchess clapped as soon as the primo uomo came onstage. This was a typical castrato’s trick, as he’d ensured that the archduchess had been told that he’d be too afraid to sing in order that the court would encourage and applaud him.'

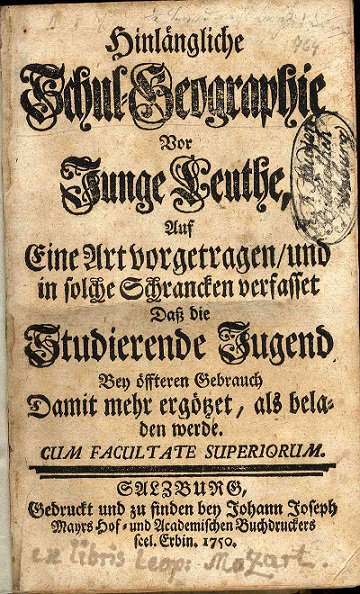

The bare facts of Mozart’s tours, however — where and when he played, who he met, what patrons or performers were helpful or difficult — hardly do justice to their importance, and not just musically. The prevailing view of them, that as far as Leopold Mozart was concerned they were chiefly engineered to exploit Mozart and make money, is belied by Leopold’s repeated assertions of their educational importance, his vivid and extended descriptions of the cultures they encountered — social, technological, and with respect to local business practices, architecture, fashion and food — and by his enlightened religiosity. He sincerely believed, as he wrote to Hagenauer from Vienna on 30 July 1768, that Wolgang was a miracle that ‘God let be born in Salzburg.’ At the same time, however, he understood that his obligation as a devout Catholic was to educate Wolfgang not only to believe, but also to be rational, to understand the world around him. As late as 1777, when Mozart was in Mannheim, Leopold wrote to him: ‘I often pointed out to you that — even if you were to remain in Salzburg until a couple of years after you’d turned twenty — you’d lose nothing because in the meantime you’d have a chance to get a taste of other useful sciences, to develop your intellect by reading good books in various languages and to practice foreign tongues.’ This idea of education, broadly conceived, was as strong a motivation for the early tours as any musical goals Leopold might have had for his children. And it was an idea he had learned as a student at the Salzburg Benedictine University in the late 1730s, where he was acquainted with Anselm Desing, a prominent philosopher and historian. Leopold owned at least one of Desing’s books, the Hinlängliche Schul-Geographie vor Junge Leuthe first published in 1750. Desing was clear why travel was a necessary, modern undertaking: it served both to educate and it allowed one to learn man’s place in God’s creation.

Title page of Desing’s Hinlängliche Schul-Geographie vor Junge Leuthe (1750)

There is no mistaking the palpable excitement in Leopold’s descriptions of the people he met, of the places he and his family visited, and of the novelty of travel. ‘To see English people in Germany is nothing to write home about’, he wrote on 28 April 1764, shortly after the family’s arrival in London. ‘But to see them in their own country and by choice is very different. The sea and especially the ebb and flow of the tide in the harbor at Calais and Dover, then the ships and, in their wake, the fish that are called porpoises rising up and down in the sea, then – as soon as we left Dover – to be driven by the finest English horses that run so fast that the servants on the coach seat could scarcely breathe from the force of the air – all this was something entirely strange and agreeable. . . our arrival overwhelmed me with so many new things.’

Observing local customs was important to Leopold, especially as they served to challenge received wisdom. When he was in Paris he wrote to Salzburg: ‘In Germany people believe mistakenly that the French are unable to withstand the cold; but this is a mistake that is revealed as such the moment you see all the shops open all winter. Not just the businessmen etc. but the tailor, shoemaker, saddler, cutler, goldsmith etc. in a word, all kinds of trades work in open shops and before the eyes of the world . . . year in, year out, whether it’s hot or cold. . . Here the women have nothing but chauffrettes under their feet: these are small wooden boxes lined with lead and full of holes, with a red-hot brick or hot ashes inside, or little earthenware boxes filled with coal.’ As for fashion, in a letter from London, Leopold wrote: ‘No woman goes out into the street without wearing a hat on her head, but these hats are very varied; some are completely round, others are tied together at the back and may be made of satin, straw, taffeta etc. All are decorated with ribbons and trimmed with lace. . . Men never go out bare headed, and a few are powdered. Whenever the street urchins see anyone decked out and dressed in a vaguely French way, they immediately call out: Bugger French! French bugger! The best policy is then to say nothing and pretend you haven’t heard. Were it to enter your head to object, the rabble would send in reinforcements and you’d be lucky to escape with only a few holes in your head. For our own part, we look entirely English.’

Jean Charles, La Chauffrette

One of the recurring themes in Leopold letters, a theme that made him reflect not only on differences between Salzburg and the world at large but also how he might himself be an agent of modernity, is engineering, especially as it related to urban geography. In a letter of 8 December 1763 from Paris he wrote to Hagenauer how struck he was that the city had no walls. So when, in 1766, it was decided to cut a tunnel through the Salzburg Mönchsberg that would ease access in and out of the city, Leopold put forward his own ideas, ideas clearly influenced by what he had observed while on tour: ‘According to the description I had, the entrance to the new gate from the town cannot be big because the entire wall in the fountain square, on which the horses are painted, is left standing. I imagine something entirely different: namely, I picture to myself that the entire wall is removed and the gate constructed in such a way that when one enters the city, the fountain is directly in front of him and he goes around it, left or right. This seems to me freer, more open, easier to navigate, more attractive and more impressive.’ A slightly later engraving shows that the original design – not Leopold’s inventive re-imagining based on his experience of urban architecture in Paris – was the one adopted.

Anon, Neutor Salzburg, c1816

In any case, science and engineering occupy a prominent place in Leopold’s letters. In London he made special note of the Chelsea waterworks, incorporated in 1723 and by the time of the Mozarts’ visit to London, supplying water to Hyde Park, St James’s Park, throughout Westminster and, from 1755, to near the Buckingham House garden wall. He also purchased an achromatic telescope by Dollond (the achromatic telescope, which eliminates chromatic aberration by using a combination of two lenses made of differing kinds of glass, thereby correcting differences in the refractive indexes for different wavelengths of light, was first patented in the late 1750s). Elsewhere in the letters he describes watches and watch mechanisms (including horizontal clocks, a novelty in London (Leopold would have bought one but was concerned that the clock-maker in Salzburg, where horizontal clocks were unknown, could not fix it if it broke), the building of military fortifications and the mechanics of new French toilets as well as modes of transportation.

Mozart’s sister Nannerl was clearly influenced by their father with respect to these encounters with the modern world; in her diary from London she described in detail much of what the family saw and in particular the recently-founded British Museum, which the Mozarts visited in July 1765: 'I saw the park and a baby elephant, a donkey with white and coffee-brown stripes, so even that they couldn’t have been painted [on] better. . . the Royal Chelsea Hospital, Westminster Bridge, Westminster Abbey, Vauxhall, Ranelagh, the Tower, Richmond, from which there is a very beautiful view, and the Royal [Botanical] Garden, Kew, and Fulham Bridge; the waterworks and a camel; Westminster Hall, the trial of Lord Byron, Marylebone; Kensington, where I saw the royal garden, the British Museum, where I saw the library, antiquities, all sorts of birds, fish. . . and plants; a particular kind of bird called a bassoon, a rattlesnake. . .; Chinese shoes, a model of the Grave of Jerusalem; all kinds of things that live in the sea, minerals, Indian balsam, terrestrial and celestial globes and all kinds of other things; I saw Greenwich . . . the Queen’s yacht, the park, where there was a very lovely view, London Bridge, St Paul’s, Southwark, Monument, the Foundling Hospital. Exchange, Lincoln’s Inn Fields Garden, Templebar, Somerset House.'

Some of the objects admired by Nannerl either survive or are known from contemporaneous pictures. The 'donkey with white and coffee-brown stripes, so even that they couldn’t have been painted [on] better' — a zebra recently brought from South Africa that was part of Queen Charlottes’s menagerie at Buckingham House — was painted by George Stubbs in 1763. It was the first zebra seen in England and, to judge by Nannerl’s description, an animal entirely unknown, except in books, to Salzburgers. The ‘model of the Grave of Jerusalem’ was almost certainly one of two models still surviving from the original collection in the British Museum of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Although Mozart was too young at the time to write down his impressions, it is probably safe to assume that he was similarly impressed by the world around him, an assumption reinforced by his later engagements with modernity. He took it upon himself to visit the famous Mannheim Observatory in 1778 and in Vienna he was friendly with the well-known scientist Ignaz von Born, head of the Masonic lodge Zu wahren Eintracht. Mozart even worked contemporaneous science into two of his operas: Despina in Così fan tutte parodies current theories of animal magnetism while the three boys in Die Zauberflöte descend to the stage in a balloon, a topical reference to the flights in Vienna in 1791 of the French balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard.

The idea that Mozart was disengaged from the modern world, and oblivious to anything other than music, is an enduring — if false — biographical trope that became common in the mid-nineteenth century. The evidence of Leopold’s letters, however, including his encouragement that Mozart learn ‘other useful sciences . . . develop your intellect by reading good books in various languages and . . . practice foreign tongues’, as well as Mozart’s own engagement with literature, technology and current affairs, suggests otherwise.

▲ [Anchor name: section_two] 1773-1780 : Mozart and Salzburg

With his return to Salzburg in March 1773 from the third Italian trip, Mozart’s time as a child prodigy was effectively over: he was now third concertmaster in the Salzburg court music establishment and more or less settled into the daily routine, both musical and social, of his native town. Although he was to travel three more times in the next eight years — to Vienna in 1773, to Munich in 1775 and, most significantly, to Mannheim and Paris in 1777-1778 — the mid- to late-1770s can justifiably be thought of as his ‘short’ Salzburg decade, not least because it was his return and later departure from there that bookended what were among the most significant times in his life, both biographically and with respect to his future career and music.

The Salzburg court music was a sprawling institution and when Leopold joined as fourth violinist in 1743, its organization was much the same as it had been at the time of its founding in 1591. In general, it was divided into four distinct and independent groups: the court music proper, which performed in the cathedral, at the Benedictine university and at court; the court- and field-trumpeters, together with the timpanists (normally ten trumpeters and two timpanists), who played in the cathedral, at court and provided special fanfares before meals and at important civic functions; the cathedral music (Dommusik), which consisted of the choral deacons (Domchorvikaren) and choristers (Choralisten) and performed in the cathedral; and the choirboys of the Chapel House (Kapellhaus), who also performed at the cathedral and who were instructed by the court musicians. The chief duty of the court music proper, together with the Dommusik and choirboys, was to perform at the cathedral. For elaborate performances, the musicians numbered about forty, sometimes more; on less important occasions the performing forces were reduced. Occasionally musicians did double duty: because the woodwind players, trumpeters and timpanists played less frequently than the strings and vocalists, they were often expected to perform on the violin and when needed, they filled out the ranks of the orchestra both at the cathedral and at court. The trumpeters and timpanists were under the control of the Oberststallmeister (the Master of the Stable); according to a court memo of 1803: ‘Their official duties are divided as follows: 'each day, two [trumpeters] sound the morning signal at court and at the court table where another plays the pieces and fanfares; accordingly, each day three [trumpeters] are in service and they are rotated every 8 days. . . For the so-called Festi palli, all the trumpeters and two timpanists are divided into two choirs, and play various fanfares in the courtyard before the court table . . . Every 3 years the trumpeters receive a uniform of black cloth with velvet trim, as well as red waistcoats with wide gold borders as well as ornamental tassles for the trumpets and gold-rimmed hats. They receive [new] trumpets every 6 years, but on festive occasions, the silversmith delivers to them silver trumpets.' The boys of the chapel house usually consisted of ten sopranos and four altos. Aside from their duties at the Cathedral, where they sang on Sundays and feast days, they also performed at the university, at local churches and occasionally as instrumentalists at court as well as receiving musical training from the court musicians: the theorist Johann Baptist Samber, Johann Ernst Eberlin, Anton Cajetan Adlgasser, Leopold Mozart and Michael Haydn all taught the choirboys. They also provided compositional opportunities: the Unschuldigen Kindleintag (Feast of the Holy Innocents) on 28 December was traditionally marked by music composed especially for the choir boys: Michael Haydn’s Missa Sancti Aloysii (for two sopranos and alto, two violins and organ) of 1777 is one example.

In addition to their service at court and at the cathedral, the court musicians performed at the Benedictine university, where school dramas were regularly given. These belonged to a long tradition of spoken pedagogical Benedictine plays which during the seventeenth century developed into an opera-like art form. Salzburg University, the most important educational institution in south Germany at the time, played a leading role in this development. At first, music in the dramas was restricted to choruses which marked the beginnings and ends of acts. By the 1760s, however, the works consisted of a succession of recitatives and arias, based at least in part on the model of Italian opera. A description from 1670 of the anonymous Corona laboriosae heroum virtuti shows the extent to which Salzburg school dramas represented a fusion of dramatic genres: ‘The poem was Latin but the stage machinery was Italian. . . . The work could be described as an opera. The production costs must have been exceptionally great. It drew a huge crowd. Part of the action was declaimed, part was sung. Gentlemen of the court performed the dances, which in part were inserted in the action as entr’actes. It was a delightful muddle and a wonderful pastime for the audience.’ Mozart’s sole contribution to the genre was Apollo et Hyacinthus, performed in 1767 between the acts of Rufinius Widl’s Latin tragedy Clementia Croesi.

The university also gave rise to an orchestral genre unique to Salzburg: the orchestral serenade. Every year in August, in connection with the university’s graduation ceremonies, the students had a substantial orchestral work performed for their professors. Typically these serenades consisted of an opening and closing march and eight or nine other movements, among them two or three concerto-like movements for various instruments. Although the origin of this tradition is not known, it was certainly established as a regular fixture of the academic year by the mid-1740s. Leopold Mozart, who composed more than thirty such works by 1757, was the most important early exponent of the genre. Wolfgang followed in his steps: K203, 204 and the so-called ‘Posthorn’ serenade K320 were all apparently written for the university. Other serenades, similar in style and substance to those for the university, were composed for name-days or, as in the case of the so-called ‘Haffner’ serenade, K250, for local weddings.

Aside from the court, Salzburg was home to several important religious institutions closely tied to, but still independent of, the state church establishment. Foremost among them was the Archabbey of St Peter’s where the music chapel consisted largely of students; only a few musicians at the abbey were professionals, among them the chori figuralis inspector, who was responsible for the music archive. Nevertheless, St Peter’s offered the court musicians numerous opportunities for both performance and composition. In 1753, Leopold Mozart composed an Applausus to celebrate the anniversary of the ordination of three fathers and some years later, in 1769, Wolfgang wrote the mass K66 for Cajetan Hagenauer, son of the Mozart’s landlord Johann Lorenz Hagenauer. Cajetan, who took the name Dominicus, was also the dedicatee of two of Michael Haydn’s works, the Missa S Dominici and a Te Deum, both composed to celebrate his election as abbot of St Peter’s in 1786.

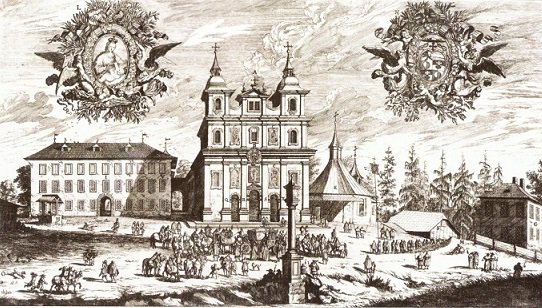

St. Peter's, Salzburg

In addition to St Peter’s, Salzburg also boasted the important convent Nonnberg, founded by St Rupert c712-4. Although strict cloistering was in effect from the late 1500s – access to the church and other external areas was walled off – some court musicians were excepted: Franz Ignaz Lipp, a contemporary of Leopold Mozart, was music teacher there and the court music copyist Maximilian Raab was cantor. The court music frequently appeared at Nonnberg for special occasions, such as the election of a new Abbess: when M. Scholastika, Gräfin von Wicka, was elected in 1766, the Archbishop celebrated her installation with a grand feast at which the court music played instrumental works and performed a cantata by Michael Haydn (Rebekka als Braut). For the most part, however, the nuns performed themselves, not only at mass, but also the fanfares traditionally given on festive occasions or to welcome guests. Perhaps the chief musical distinction of Nonnberg and other local churches was the performance of German sacred songs. Such works were composed and printed in Salzburg as early as the first decade of the eighteenth century, including the anonymous Dreyssig Geistliche Lieder (Hallein, 1710) and Gotthard Wagner's Cygnus Marianus, Das ist: Marianischer Schwane (Hallein, 1710). These songs, frequently performed instead of an offertory, continued to be written throughout the century, some of them by Salzburg's most important composers, including Eberlin and Leopold Mozart. More importantly, the cultivation at Nonnberg of German sacred songs provided opportunities for women composers since aside from singing at court, women in Salzburg had little opportunity to shine musically, no matter how exceptional they may have been.

Numerous religious institutions near Salzburg also maintained close contact with the court and other music establishments within the city. These included the Benedictine monastery at Michaelbeuern, four of whose abbots were rectors at the Salzburg University, and some of whose musicians, among them Andreas Brunmayer, studied in Salzburg and remained there as part of the court music; and the Benedictine monastery at Lambach, which purchased music and musical instruments from Salzburg and maintained close ties with the Salzburg court and the Salzburg court musicians: both Michael Haydn and Leopold Mozart were welcome guests at Lambach. Other institutions allied with Salzburg stretched up the Salzach, along what is now the border with Bavaria, among them Landshut, Tittmoning, Frauenwörth, Wasserburg am Inn and Beuerberg. All of these institutions relied heavily on the city for both music and musicians.

Finally, civic music making played an important part in Salzburg’s musical life. Watchmen blew fanfares from the tower of the town hall and were sometimes leased out to play for weddings, while military bands provided marches for the city garrisons. Often there was a close connection with the court: it was the watchmen, not the court music, that played trombones in the cathedral during service. And private citizens, including court musicians off duty, were active musically as well. Concerts to celebrate name-days and serenades to celebrate weddings were common, as was domestic music-making generally. In a letter of 12 April 1778, Leopold Mozart wrote: ‘on evenings when there is no grand concert, he [the soprano Francesco Ceccarelli] comes over with an aria and a motet, I play the violin and Nannerl accompanies, playing the solos for viola or for wind instruments. Then we play keyboard concertos or a violin trio, with Ceccarelli taking the second violin.’ In the same letter, Leopold reports to Mozart that a member of the local nobility, Johann Rudolf Czernin, had started up a private orchestra.

Carl Schneeweiß, Military Parade on the Residenzplatz, Salzburg, 1756

Little is known about Mozart’s day-to-day life in Salzburg, especially during the years immediately following his return from the third Italian trip. Hieronymus Colloredo had been elected prince-archbishop of Salzburg on 14 March 1772 — Mozart’s Il sogno di Scipione was probably performed as part of the celebrations celebrating his accession — and on 21 August 1772 Wolfgang was appointed paid third concertmaster in the Salzburg court music. Financially, the family prospered: in late 1773 they moved from their apartment in the Getreidegasse, where they had rented from the Hagenauers, to a larger one, the so-called Tanzmeisterhaus in the Hannibalplatz (now the Makartplatz). But even before their move, in July 1773, Leopold had taken Wolfgang to Vienna, where there were rumours of a possible opening at the imperial court. Nothing came of this but the trip, which lasted four months, was a productive one: Mozart composed the serenade K185, probably intended for the Salzburg university graduation of a family friend, Judas Thaddäus von Antretter, and six quartets K168-K173, possibly in reaction to Haydn’s latest quartets, opp. 9, 17 and 20, and the prevailing fashion for quartets in Vienna at the time, especially those with a Sturm und Drang element and more elaborate contrapuntal writing than had been usual up to that time.

Quartets were not much cultivated in Salzburg, but other kinds of works were and Mozart composed prolifically during the years 1772-1774 in genres that were either popular or required locally: the masses K167, K192 and K194; the litanties K125 and K195 together with the the Regina coeli K127; and more than a dozen symphonies (K124, 128, 129, 130,132, 133, 134, 161+163, 162, 181, 182, 183, 184, 199, 200, 201 and 202) as well as the keyboard concerto K175, the concertone for two solo violins K190, the serenade K203, the divertimentos K131, K166 and K205 and the string quintet K174. He may also have composed an organ concerto, since according to a contemporaneous account from 1774 of the celebrations surrounding the one hundredth anniversary of the pilgrimage church Maria Plain, just outside Salzburg as a contemporaneous diary reports: ‘Today there was particularly beautiful and agreeable music the the high mass at Maria Plain; primarily because it was produced almost exclusively by the princely court musicians, and especially by the older and younger, both famous, Mozarts. The young Herr Mozart played an organ and a violin concerto, to everyone’s amazement and astonishment.’ Later that year, in December, he traveled to Munich for the composition and première (on 13 January 1775) of his opera buffa La finta giardiniera and probably composed the six keyboard sonatas K279-K284. The following April he wrote the serenata Il re pastore K208 for the visit to Salzburg of Archduke Maximilian Franz on 23 April.

Melchior Küsel, Consecration of the Maria Plain Pilgrimage Basilica, Salzburg 1674 (original: Salzburg Museum)

With some exceptions – among them the keyboard concertos K242 and K246, written for the Lodron and Lützow families, respectively, and the “Haffner” serenade K250 – it is not entirely clear for whom Mozart composed much of his instrumental music or when it was performed. Almost certainly, though, much of it was written for family and friends, for dances or for special occasions such as weddings and namedays, as several entries from the diary of the family friend Johann Baptist Joseph Joachim Ferdinand von Schiedenhofen show:

18 February 1776: In the evening I again went to the ball, where there were 320 masqueraders. I went at first as a Tyrolean girl. Among the curiousities was an operetta by Mozart, and a peasant’s wedding. I remained until 4.30 and dancing continued until 5.30.

18 June 1776: After dinner to the music composed by Mozart for Countess Ernst Lodron. K247?

7 July 1776: We went together to the music-making at Frau von Antretter’s. Thence I went home in the company of the Mozarts.

21 July 1776: After dinner I went to the bridal music which young Herr Haffner had made for his sister Liserl. It was by Mozart and was performed in the summer house at Loretto. K250

22 August 1776: I went . . . for a walk with Carl Agliardi and others, and there was also music at Mozart’s.

Mozart continued to compose prolifically during the period 1775-177 — his works from that time include the masses K220, 257-259, 262 and 275, the litany K243 and the offertory K277, the violin concertos K211, 216, 218 and 219, the keyboard concertos K238, 242, 246 and 271, the serenades K204 and 250 and numerous divertimentos, among them K188, 240, 247 and 252 — but his rejection of court musical life was transparent. Not only does much of his instrumental music appear to have been written for family and friends, but his output of church music, while significant in quality, was meagre compared to that of his colleague Michael Haydn. The root cause of the Mozarts’ dissatisfaction in Salzburg remains unclear, even if Leopold Mozart’s letters document his frustrating inability to find suitable positions for both of them and he was annoyed that Italian musicians at court, chiefly the Kapellmeisters and singers, were better paid, and more favoured, than local talent. (Even before Colloredo’s reign, Leopold had lamented the power and influence of Italian musicians throughout Germany: in 1763 he attributed his failure to secure an audience with Duke Carl Eugen of Württemberg to the intrigues of his Kapellmeister Jomelli, and in 1764 he wrote to Hagenauer from Paris, ‘If I had one single wish that I could see fulfilled in the course of time, it would be to see Salzburg become a court which made a tremendous sensation in Germany it is own local people.’) And while some changes introduced by Colloredo after his election, including educational reforms and the establishment of a public theatre in the Hannibalplatz for both spoken drama and opera, favoured cultural life in the city by attracting prominent writers and scientists, others eliminated some traditional opportunities for music-making both at court and at the cathedral. The university theatre, where school dramas had been performed regularly since the seventeenth century, was closed in 1778, the mass was generally shortened and restrictions were placed on the performance of purely instrumental music as well as some instrumentally accompanied sacred vocal music at the cathedral and other churches. Concerts at court were curtailed.

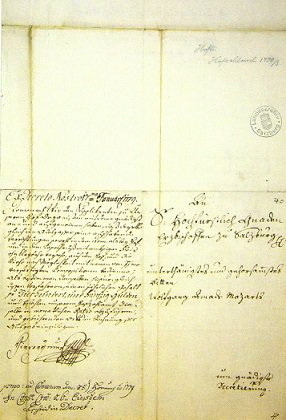

The Mozarts’ grievances notwithstanding, there is no compelling evidence that Colloredo mistreated the Mozarts, at least early in his reign. Wolfgang’s Il sogno di Scipione was performed as part of the festivities surrounding Colloredo’s enthronment; Mozart had been formally taken into paid employment at court; Leopold continued to run the court music on a periodic basis and was entrusted with hiring musicians and purchasing both music and musical instruments; and father and son had been allowed to travel to Italy, Vienna and Munich. Nevertheless, matters came to a boiling point in the summer of 1777 and in August Mozart wrote a petition asking the archbishop for release from his employment:

Your Serene Highness

most worthy Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, most gracious Ruler and

Lord!

I have no need to importune Your Serene Highness with a circumstantial description of our sad situation: my father, in all honour and conscience, and with every ground of truth, has declared this in a petition most submissively placed before Your Serene Highness on 14 March last. Since however Your Highness's favourable decision did not ensue, as we had hoped, my father would have submissively begged Your Serene Highness as early as June graciously to allow us a journey of several months, in order somewhat to rehabilitate us, had not Your Highness been pleased to command that all members of his Music hold themselves in readiness for the impending visit of His Majesty the Emperor. My father again humbly asked for this permission later; but Your Serene Highness refused him this and graciously observed that I, being in any case only on part-time service, might travel alone. Our circumstances are pressing: my father decided to send me off by myself. But to this too Your Serene Highness made some gracious objections. Most gracious Sovereign Prince and Lord! Parents takes pains to enable their children to earn their own bread, and this they owe both to their own interest and to that of the state. The more of talent that children have received from God, the greater is the obligation to make use thereof, in order to ameliorate their own and their parents' circumstances, to assist their parents, and to take care of their own advancement and future. To profit from our talents is taught us by the Gospel. I therefore owe it before God and in my conscience to my father, who indefatigably employs all his time in my upbringing, to be grateful to him with all my strength, to lighten his burden, and to take care not only of myself, but of my sister also, with whom I should be bound to commiserate for spending so many hours at the harpsichord without being able to make profitable use of it.

May Your Serene Highness graciously permit me, therefore, to beg most submissively to be released from service, as I am obliged to make the best use of the coming September, so as not to be exposed to the bad weather of the ensuing cold months. Your Serene Highness will not take this most submissive request amiss, since already three years ago, when I begged for permission to travel to Vienna, Your Highness was graciously pleased to declare that I had nothing to hope for and would do better to seek my fortune elsewhere. I thank Your Serene Highness in the profoundest devotion for all high favours received, and with the most flattering hope that I may serve Your Serene Highness with greater success in the years of my manhood, I commend myself to your continuing grace and favour as

Your Serene Highness's

my most gracious Sovereign Prince and

Lord's

most humble and obedient Wolfgang Amade Mozart.

In what can only be described as spitefulness — and at the same time at least some evidence of the archbishop’s part in the breakdown of Mozart’s relationship with Salzburg — Colloredo dismissed both father and son. Leopold, however, felt he could not afford to leave Salzburg and so Mozart set out with his mother on 23 September. The purpose of the trip was for Mozart to secure well-paid employment, preferably at Mannheim, which Leopold described in a letter of 13 November 1777 as 'that famous court, whose rays, like those of the sun, illuminate the whole of Germany.'

Mozart called first at Munich, where he offered his services to the elector but met with a polite refusal. In Augsburg he embarked on a relationship with his cousin, Maria Anna Thekla (the "Bäsle"), with whom he later engaged in a scatological correspondence, and gave a concert including several of his recent works that was reviewed in the Augsburgische Staats- und Gelehrten Zeitung for 28 October 1777:

The evening of Wednesday last was one of the most agreeable for music-lovers. Herr Chevalier Mozart, a son of the famous Salzburg musician, who is a native of Augsburg, gave a concert on the fortepiano in the hall of Count Fugger. As Herr Stein happened to have three instruments of the kind ready, there was an opportunity to include a fine concerto for three fortepianos, in which Herr Demler, the cathedral organist, and Herr Stein himself played the other two keyboard parts. Apart from this the Chevalier played a sonata and a fugued fantasy without accompaniment, and a concerto with one, and the opening and closing symphonies were of his composition as well. Everything was extraordinary, tasteful and admirable. The composition is thorough, fiery, manifold and simple; the harmony so full, so strong, so unexpected, so elevating; the melody, so agreeable, so playful, and everything so new; the rendering on the fortepiano so neat, so clean, so full of expression, and yet at the same time extraordinarily rapid, so that one hardly knew what to give attention to first, and all the hearers were enraptured. One found here mastery in the thought, mastery in the performance, mastery in the instruments, all at the same time. One thing always gave relief to another, so that the numerous assembly was displeased with nothing but the fact that pleasure was not prolonged still further. Those patriotically minded had the especial satisfaction of concluding from the stillness and the general applause of the listeners that we know here how to appreciate true beauty—to hear a virtuoso who may place himself side by side with the great masters of our nation, and yet is at least half our own. . .'.

From Augsburg Mozart and his mother moved on to Mannheim where they remained until the middle of March 1778. Wolfgang became friendly with the concert master Christian Cannabich, the Kapellmeister Ignaz Holzbauer and the flautist Johann Baptist Wendling, and he recommended himself to the elector but without success. Ferdinand Dejean, an employee of the Dutch East India company, asked him to compose three flute concertos and two flute quartets. Mozart failed to fulfil the commission and may have written only a single quartet (K285). But he was not compositionally idle: his works from Mannheim include the piano sonatas K309 and K311, five unaccompanied sonatas (K296, K301-303 and K305), and two arias, Alcandro lo confesso–Non sò d’onde viene K294, composed for Aloysia Lange, the daughter of the Mannheim copyist Fridolin Weber, and Se al labbro mio non credi–Il cor dolente K295. Mozart was in love with Aloysia and wrote to Leopold of his idea to take her to Italy to become a prima donna, but this proposal infuriated his father, who accused him of irresponsibility and family disloyalty.

Mozart and his mother arrived at Paris on 23 March 1778. There he composed additional music, mainly choruses (now lost) for a performance of a Miserere by Holzbauer and, according to his letters home, a sinfonia concertante, K297B, for flute, oboe, bassoon and horn; both works are lost. He had a symphony, K297, performed at the Concert Spirituel on 18 June (for a later performance Mozart rewrote the slow movement) and wrote part of a ballet, Les petits riens, for the ballet master Jean-Georges Noverre that was given with Niccolò Piccinni’s opera Le finte gemelle. But Mozart was unhappy in Paris. He claimed to have been offered, but to have refused, the post of organist at Versailles and his letter of 1 May, concerning the unperformed sinfonia concertante, makes it clear that, justified or not, he suspected malicious intrigues against him:

There’s another snag with the sinfonia concertante . . . and [I think] that I again have my enemies here. Where haven’t I had them? – But it’s a good sign. I had to write the sinfonia in the greatest haste but I worked very hard, and the 4 soloists were and still are head over heels in love with it. Legros kept it for 4 days in order to have it copied, but I always found it lying in the same place. Finally – the day before yesterday – I couldn’t find it but had a good look among the music and found it hidden away. I feigned ignorance and asked Legros: By the way, have you already given the sinf. concertante to the copyist? – No – I forgot. I can’t, of course, order him to have it copied and performed, so I said nothing. I went to the concert on the 2 days when it should have been played. Ramm and Punto came over to me, snorting with rage, and asked why my sinfonia concert. wasn’t being given. – I don’t know. That’s the first I’ve heard about it. No one ever tells me anything. Ramm flew into a rage and cursed Legros in the green room in French, saying that it wasn’t nice of him etc. What annoys me most of all about the whole affair is that Legros never said a word to me about it, I wasn’t allowed to know what was going on – if he’d offered me some excuse, saying that there wasn’t enough time or something similar, but to say nothing at all – but I think that Cambini, one of the Italian maestri here, is the cause because in all innocence I made him look foolish in Legros’ eyes at our first meeting.

Mozart’s mother fell ill about mid-June and despite attempts to secure proper medical treatment died on 3 July. Wolfgang took up residence with Grimm, the family’s patron from their two earlier stays in Paris, and on 31 August Leopld wrote to Wolfgang to inform him that following the death of the Anton Cajetan Adlgasser, a post was open to him in Salzburg as court organist with accompanying duties rather than as a violinist; Colloredo had offered Mozart an increase in salary and generous leave. Mozart set out on 26 September and traveling circuitously by way of Nancy, Strasbourg and Mannheim (where he was received coolly by Aloysia Weber, who was now singing in the court opera), he arrived home in the third week of January 1779. His new duties in Salzburg included playing in the cathedral and at court, and instructing the choirboys. He composed the ‘Coronation’ mass K317, the missa solemnis K337, two vespers settings, K321 and K339 and the Regina coeli K276 as well as several instrumental works including the concerto for two pianos K365, the sonata for piano and violin K378, three symphonies (K318, K319 and K338), the ‘Posthorn’ serenade K320, a sinfonia concertante for violin and viola K364, and incidental music for Thamos, König in Ägypten and Zaide.

Anonymous, Aloysia Weber, c1780

In the summer of 1780, Mozart received a commission to compose a serious opera for Munich and engaged the Salzburg cleric Giovanni Battista Varesco to prepare a libretto based on Antoine Danchet’s Idomenée of 1712. He began to set the text in Salzburg since he already knew several of the singers from Mannheim and left for Munich only in early November. The opera was given on 29 January 1781 to considerable success and both Leopold and Mozart’s sister, Nannerl, who had traveled from Salzburg, were in attendance. The family remained in Munich until mid-March, during which time Mozart also composed the recitative and aria Misera! dove son–Ah! non son’ io che parlo K369, the oboe quartet K370. The three piano sonatas K330-332 may also date from this time, or from a few months later.

The death of Mozart’s mother in Paris on 3 July 1778 and the ensuing, sometimes-recriminatory letters between father and son — Leopold accused Mozart of lying and improper attention his mother — is generally taken to represent the first and most compelling evidence of an irreparable family rupture that had its roots in Leopold’s alleged exploitation of Wolfgang as a child both for profit and for his own self-aggrandisement. There is no evidence, however, that anyone at the time thought Leopold to be less than a loving, intelligent parent whose only fault, perhaps, was to overindulge Wolfgang. Johann Adam Hiller wrote in his Wochentliche Nachrichten und Anmerkungen die Musik betreffend, published at Leipzig on 25 November 1766, that ‘Such precocious virtuosi certainly do much honour to their father, since they have attained to all this through his instruction; and since he knew how to discover easy ways and means of making a matter comprehensible and easy for children which at times is not readily grasped by older and adult persons’ while the composer Johann Adolph Hasse wrote to the Venetian composer and philosopher Giovanni Maria Ortes on 30 September 1769 that ‘The said Sig. Mozard is a very polished and civil man, and the children are very well brought up. . . I am sure that if his [Wolfgang’s] development keeps due pace with his years, he will be a prodigy, provided that his father does not perhaps pamper him too much or spoil him by means of excessive eulogies; that is the only thing I fear.’ Similarly, the music historian Charles Burney, who met the family in Bologna in August 1770 while Mozart was working on Mitridate, noted that ‘[I] shall be curious to know how this extraordinary boy acquits himself in setting words in a language not his own. But there is no musical excellence I do not expect from the extraordinary quickness and talents, under the guidance of so able a musician and intelligent a man as his father. . .’

Certainly Leopold was sometimes given to insensitivity, even harshness. On 24 November 1777, when Mozart and his mother were in Mannheim, Leopold wrote to them: ‘A journey like this is no joke, you’ve no experience of this sort of thing, you need to have other, more important thoughts on your mind than foolish games, you have to try to anticipate a hundred different things, otherwise you’ll suddenly find yourself in the shit without any money, – – and where you’ve no money you’ll have no friends either, even if you give a hundred lessons for nothing, and even if you write sonatas and spend every night fooling around from 10 till 12 instead of devoting yourself to more important matters. Then try asking for credit! – That’ll wipe the smile off your face. I’m not blaming you for a moment for placing the Cannabichs Cannabichs under an obligation to you by your acts of kindness, that was well done: but you should have devoted a few of your otherwise idle hours each evening to your father, who is so concerned about you, and sent him not simply a mishmash tossed off in a hurry but a proper, confidential and detailed account of the expenses incurred on your journey, of the money you still have left, of the journey you plan to take in future and of your intentions in Mannheim etc. etc. In short, you should have sought my advice; I hope you’ll be sensible enough to see this, for who has to shoulder this whole burden if not your poor old father?’ And he was could be manipulative, writing to Wolfgang on 19 October 1778: ‘The main thing is that you return to Salzburg now. I don’t want to know about the 40 louis d’or that you may perhaps be able to earn. Your whole plan seems to be to drive me to ruin, simply in order to build your castles in the air. . . In short, I have absolutely no intention of dying a shameful death, deep in debt, on your account; still less do I intend to leave your poor sister destitute. . . Until now I’ve written to you not only as a father but as a friend; I hope that on receiving this letter you will immediately expedite your journey home and conduct yourself in such a way that I can receive you with joy and not have to greet your with reproaches. Indeed, I hope that, after your mother died so inopportunely in Paris, you’ll not have it on your conscience that you contributed to your father’s death, too.’

But these are not the only letters that passed between father and son and they were written under trying circumstances: the first significant separation of Leopold and Wolfgang, Mozart’s awkward attempts to succeed on his own, and a shared, intense dislike of Salzburg exacerbated by their failure to find employment elsewhere, all at a time when Leopold, for the first time, must have felt himself an ineffectual bystander to Wolfgang’s life. Under different, less fraught circumstances — but no less telling of the relationship between them for that — Mozart and his father exchanged letters of a profoundly intimate and loving cast. On 25 September 1777, Leopold wrote to Wolfgang and Maria Anna about the day they had left for Mannheim and Paris:

My dears, After you’d left, I came upstairs very wearily and threw myself into an armchair. I made every effort to curb my feelings when we said goodbye, in order not to make our farewell even more painful, and in my daze forgot to give my son a father’s blessing. I ran to the window and called after you but couldn’t see you driving out through the gates, so we thought you’d already left as I’d been sitting for a long time, not thinking of anything. Nannerl was astonishingly tearful and it required every effort to comfort her. She complained of a headache and terrible stomach pains, finally she started to be sick, vomiting good and proper, after which she covered her head, went to bed and had the shutters closed, with poor Pimpes beside her. I went to my own room, said my morning prayers, went back to bed at half past 8, read a book, felt calmer and fell asleep. The dog came and I woke up. He made it clear that he wanted me to talk him for a walk, from which I realized that it must be nearly 12 o’clock and that he wanted to be let out. I got up, found my fur and saw that Nannerl was fast asleep and, looking at the clock, saw that it was half past 12. When I got back with the dog, I woke Nannerl and sent for lunch. Nannerl had no appetite at all; she ate nothing, went back to bed after lunch and, once Herr Bullinger had left, I spent the time praying and reading in bed. By the evening Nannerl felt better and was hungry, we played piquet, then ate in my room and played a few more rounds after supper and then, in God’s name, went to bed. And so this sad day came to an end, a day I never thought I’d have to endure.’

To celebrate Leopold’s name day, on 8 November 1777 Mozart wrote to his father from Mannheim: