The Mozarts were surrounded by art: in their home and the homes of their friends and acquaintances, at mansions and palaces they visited, at churches and other religious institutions, at inns and taverns and even on the street, including ballad sheets and other engravings hawked by itinerant merchants or established tradesmen. Some of their letters explicitly describe the art they saw: Leopold marveled at the Flemish and Dutch art the family saw in Brussels, Antwerp and elsewhere. And in 1778, Mozart’s mother, Anna Maria, took it upon herself to visit the gallery at the Palais Luxembourg in Paris, the first public art gallery in France.

Andrea del Sarto, Charity, 1518, exhibited at Palais Luxembourg from 1750 and seen by Anna Maria Mozart in 1778 (now Paris, The Louvre)

Most of what the Mozarts saw, however, is not mentioned in the letters although it can be reconstructed from early documents such as the estate inventories and the history of museums and other institutions Mozart visited or frequented, including the ceiling frescoes, tapestries and paintings that adorned the archbishop’s residence in Salzburg, the art that ornamented the palace of Versailles or the Brussels cathedral or the Hofburg in Vienna, among many others. Given Mozarts’ widespread exposure to art of all sorts, their experiences were both varied and nuanced, historical and modern, aesthetic or utilitarian, and intersected with the broader cultures they lived and worked in or visited.

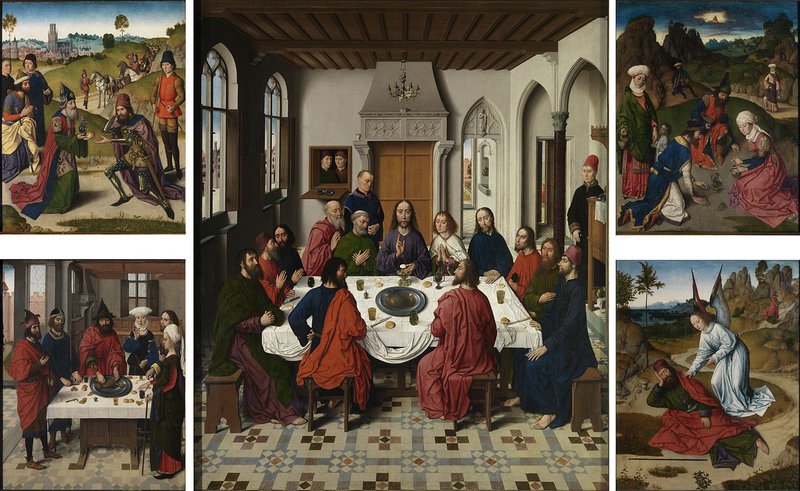

Leuven 1763: Victor Honoré Janssens, Last Supper

Brussels 1763: Peter Paul Rubens, Christ’s Charge to Peter

Antwerp 1765: Peter Paul Rubens, Descent from the Cross

Leuven 1763: Victor Honoré Janssens, Last Supper

Leuven 1763: Victor Honoré Janssens, Last Supper

The Mozarts stopped at Leuven (Louvain) for one day, 4 October 1763. Later that month, after their arrival in Brussels, Leopold wrote to Johann Lorenz Hagenauer (letter of 17 October-4 November 1763):

- Here we saw the first of the most beautiful and magnificent marble altars and the priceless paintings by famous Dutch artists. I can’t give you a detailed description as it would take too long and I don’t have the time. I was stopped in my tracks by one piece, which represented the Last Supper.

According to Mozart. Breife und Aufzeichnungen (v.85), this painting was the middle panel of an altar by Dirk Bouts commissioned in 1464.

Dirk Bouts, Last Supper (Sint-Pieterskerk, Leuven)

In fact, the wings of the Bouts triptych were sold prior to the Mozarts’ visit there and the central panel representing the last supper removed from its altar to form part of a framed montage of early painting decorating the space above the entrance to the sacristy of the Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament[1]. The painting Leopold admired was probably the altarpiece by Victor Honoré Janssens (1658-1738) that was commissioned to replace the Bouts. The Janssens is now lost but is described in Jean-Baptiste Descamps, Voyage pittoresque de la Flandre et du Brabant, Avec Réflexions relativement aux Arts & quelques Gravures (Paris, 1769), 102:

- Dans la Chapelle de la Communion, à la gauche du Choeur, est un Autel considérable de beau marbre, avec des colonnes torses bien exécutées. Le Tableau du milieu représentant la Cene, est peint par A. Janssens . . . la composition est sçavante & spirituelle, le dessein est correct, mais tout y est poussé au noir.

- In the Communion Chapel, to the left of the choir, is a substantial altar of excellent marble, with well executed twisted columns. The picture in the middle, representing the Last Supper, was painted by A. [sic] Janssens . . . its composition is skilled and pious, its drawing is accurate, but everything is forced into darkness.’

Further, see Thomas Tolley, ‘Developing an eye for harmony: Rubens in Mozart’s education’ in Late Eighteenth-Century Music and Visual Culture, ed. Cliff Eisen and Alan Davison (Turnhout, 2017), 71-110

Brussels 1763: Peter Paul Rubens, Christ’s Charge to Peter

Brussels 1763: Peter Paul Rubens, Christ’s Charge to Peter

In his letter from Brussels dated 17 October-4 November 1763, Leopold wrote to Johann Lorenz Hagenauer: ‘I can’t stop thinking about a painting by Rubens that’s in the main church. In it Christ can be seen handing the keys to Peter in the presence of other apostles[2]. The figures are life-size.’

Peter Paul Rubens, Christ’s Charge to Peter (London, Wallace Collection)

Painted c1616, Rubens’s Christ’s Charge to Peter, now at the Wallace Collection, London, was acquired by Richard Seymour-Conway, 4th marquess of Hertford (1800-1870) in 1850; it subsequently passed to Julie-Amélie-Charlotte Castelnau, Lady Wallace, widow of Sir Richard Wallace (1818-1890, believed to be the illegitimate son of Richard Seymour-Conway,) who in 1897 bequeathed it to the nation[3].

The painting, commissioned for the tomb of Nicholas Damant (c1531-1616) at the Kathedraal van Sint-Michiel en Sint-Goedele, Brussels, conflates two biblical episodes: in the Gospel according to St John (xxi:15-17), Christ demands that Peter ‘feed my sheep’; in the Gospel according to St Matthew (xvi:13-19), Christ promises to present Peter with the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven[4]. It was considered one of the chief masterpieces at the cathedral. According to Jean-Baptiste Descamps, Voyage pittoresque de la Flandre et du Brabant, Avec des Réflexions relativement aux Arts & quelques Gravures (Paris, 1769), 57:

- En entrant dans la Chapelle du Saint Sacrement, le Tableau du premier petit Autel, à la droite, représente Saint Pierre, accompagné de deux Apôtres, qui reçoit les clefs de Notre-Seigneur, peint par Rubens. . . Ce Tableau [est] plus lissé que les beaux ouvrages de ce Maître. . . les têtes sont très-belles & d'une couleur admirable: ce beau Tableau a l'air de sortir des mains de l'Artiste, tant il et bien conservé & frais.

- On entering the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, the painting on the first small altar, on the right, represents Saint Peter, accompanied by two apostles, who receives the keys of Our Lord, painted by Rubens. . . This painting [is] among the most brilliant of the beautiful works of this master. . . the heads are very beautiful & of an admirable colour: this beautiful picture seems to come straight from the hands of the artist, as it is and well preserved & fresh.

Antwerp 1765: Peter Paul Rubens, Descent from the Cross

Antwerp 1765: Peter Paul Rubens, Descent from the Cross

On 19 September 1765, Leopold Mozart wrote to Johann Lorenz Hagenauer from The Hague, describing the family’s visit to Antwerp during the second week of September:

- We spent 2 days in Antwerp as it was a Sunday. Wolfgang played on the main organ in the cathedral[5]. NB: There are some really good organs in Flanders and Brabant. Above all, however, there’s a lot that could be said about the paintings here, which are quite exquisite. Antwerp especially is the place for them. We visited all the churches[6]. I’ve never seen as much black and white marble and such a surfeit of outstanding paintings, especially by Rubens, as I did here and in Brussels. Above all, Rubens’s Descent from the Cross in the main church in Antwerp surpasses everything you could ever imagine.’

Peter Paul Rubens, Descent from the Cross (Antwerp, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal)

Rubens’s Descent from the Cross, commissioned in 1611 by the Antwerp Confraternity of Arquebusiers, is the central panel of a triptych at the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp. Completed in 1614, it was a significant attraction for tourists and art lovers from the seventeenth century on. A description from Mozart’s time can be found in An Accurate Description of the Principal Beauties, in Painting and Sculpture, belonging to the several Churches, Convents, &c.in and about Antwerp. Together with a General Account of the Site, Fortifications, Streets, and Buildings of that ancient City; and an Historical Detail of the memorable Events which have happened to it, from its Foundation to the present Time (London, 1765), 8-9:

- The next curiosity worthy attention is the picture over the fusiliers altar, which is a representation of Christ taken down from the cross. This is looked upon as one of Rubens’s masterpieces. This grand performance has two folding doors before it, on one of which is represented the visitation, and on the other the purification of the Blessed Virgin. On the inside of one of them is painted St. Christopher, carrying the child Jesus across a river: on the inside of the other is painted a hermit, with his eyes fixed on that saint. The whole is executed by Rubens. Just at the feet of the saint, on the surface of the water, is a fish, called in the Flemish tongue, a bot, a term signifying a blockhead; and on the top of the hermit’s lantern is perched an owl. By this, Rubens tacitly answered the envious query . . . of Vencenlas Coeberger, who had painted a fellow with a large plaister on his head, and demanded of Rubens, with s sneer, whether he could cure the man’s wound or, in other terms, whether he could improve his picture? Rubens, by painting the fish and the owl just mentioned, makes the following arch reply, “You ignorant blackhead! You owl! If you have any eyes in your head, you may see that this picture infinitely surpasses yours.”

Portraits

Portraits

Earl of Shaftesbury

William Hazlitt

Mozart Family (Della Croce)

Madame de Pompadour (de la Tour)

Madame de Pompadour with clavecin (Boucher)

Louis XV (van Loo)

Increasingly throughout the eighteenth-century, portraiture, whether institutional or personal, for reasons of state or merely private ownership and contemplation, was seen as an important art form. In 1732, Anthony, earl of Shaftesbury, described portraiture as primarily a mimetic art, the accurate rendering of a sitter’s social status through his or her physiognomy and dress and a representation of the sitter’s property or other symbols. By century’s end, however, William Hazlitt claimed for portraiture a representation of the ‘essence of the sitter, reflect[ting] his thoughts and feelings, the capturing on canvas of subjectivity.’

Earl of Shaftesbury Hazlitt

British School, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, third Earl of Shaftesbury (Shaftesbury Town Hall) // William Hazlitt, Self-Portrait c1802 (Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery)

Some of the portraits seen by the Mozarts, especially those in the homes of the nobility, conformed to the earl of Shaftesbury’s notions about portraiture. Others, however, and in particular portraits of Mozart himself executed in the 1780s, are informed by Hazlitt’s view. Consequently, the different portraits seen or collected by the Mozarts meant different things to them. Some were aides-mémoires of their travels (such as the portrait of Ferdinand IV of Naples or the topographical engravings they collected in Italy); some were personal mementoes of their family life, such as the family portrait executed 1779/1780, possibly by Della Croce; and some, such as portraits of Madame Pompadour and Louis XV, they saw as manifestations of royal wealth and privilege, as expressing something, in this particular case about French society, just as portraits of other monarchs reflected on their wealth and privilege.

Mozart Family (Della Croce)

Della Croce (attr.), The Mozart Family, 1779-1780 (Salzburg, Mozart Museums)

Madame Pompadour and Louis XV: Paris, 1764

On 1 February 1764, Leopold wrote to Salzburg from Paris:

- I expect you’d like to know what Madame Marquise Pampadour [Pompadour] looks like, wouldn’t you? – – She must once have been very beautiful since she’s still attractive. She’s tall and stately in her appearance, fat or, rather, plump, but very well proportioned and blonde and looks a lot like the late Tresel Freysauf [Freysauff], while her eyes have a certain similarity to those of Her Majesty the Empress [Maria Theresia]. She does herself great credit and is exceptionally intelligent. Her apartments at Versailles, which look out on the gardens, are a veritable paradise; in Paris she has a magnificent mansion that’s been entirely rebuilt in the Faubourg St Honoré. In the room that contains the clavecin |: which is all gilt and most elaborately lacquered and painted :| there’s a life-size portrait of her and next to it a portrait of the king.

Considering that Leopold was able to describe in some details two portraits as well as Madame Pompadour’s harpsichord, the Mozarts must have visited Madame Pompadour’s mansion at 55 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré (now the Élysée Palace) sometime in late 1763 or early 1764. The life-size portrait of her may be the one executed by Maurice-Quentin de La Tour c1756 (Louvre, Paris).

Madame de Pompadour (de la Tour)

Quentin de La Tour, Madame Pompadour c1756 (Louvre, Paris)

With respect to the portrait of Madame Pompadour, the Louvre notes:

-

The marquise is seated in a collector's cabinet decorated with blue-green paneling accented in gold. The sumptuousness of her clothing - a spectacular French-style dress in fashion around 1750 - shows a tendency to ostentation, while the absence of jewelry and the simplicity of her coiffure underscore the portrait's personal nature. She is shown as a protector of the arts, surrounded by attributes symbolizing literature, music, astronomy and engraving. Arranged on a table next to her in a splendid still life are Guarini's Pastor Fido, the Encyclopédie, Montesquieu's De l'esprit des lois, Voltaire's La Henriade, a globe, and Le Traité des pierres gravées by Pierre-Jean Mariette. Lastly, there is an engraving by the Count de Caylus, which, however, Delatour has signed "Pompadour sculpsit": an allusion to the marquise's fondness for engraving and her own creations in this art form. The presence of references to the arts and literature should be read here as an educational program. Still in love with Louis XV, she hoped to bring about in him a transformation through exposure to the extraordinary intellectual, moral, and philosophical developments which animated Paris at that time but which failed to reach the court, frozen as it was in principles and codes of etiquette.

It is certain that the king saw this portrait; but did he grasp the double meaning of the works the marquise selected? While what was said between the two friends will always remain a mystery, the king clearly did not implement the liberal program suggested by his mistress.

(https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/full-length-portrait-marquise-de-pompadour)

Madame Pompadour’s clavecin can be seen in a portrait by François Boucher, also at the Louvre:

Madame de Pompadour (Boucher)

François Boucher, Madame Pompadour, c1750-1755 (Louvre, Paris)

Louis XV (van Loo)The portrait of Louis XV, executed by Jean-Baptiste van Loo c1723, is now at Versailles.

Jean-Baptiste van Loo, Louis XV, c1723 (Palace of Versailles)

[1] Micheline Comblen-Sonkes, The Collegiate Church of Saint Peter, Brussels, 1996, 49-52.

[2] Christ's Charge to Peter (c1616), commissioned for the tomb of Nicholas Damant (c1531–1616) in the collegiate of SS Michel and Gudule, now at The Wallace Collection, London.

[3] For a history of the Wallace Collection, see https://www.wallacecollection.org/collection/history-collection/.

[4] https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/christs-charge-to-peter-209730 [accessed 5 July 2020].

[5] Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal; the organ on which Mozart played does not survive.

[6] These may have included the St. Carolus Borromeuskerk, Sint-Pauluskerk and Sint-Jacobskerk in addition to the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal.

[7] Maria Theresia.

[8] Presumably the harpsichord pictured in François Boucher’s c1750 portrait of Madame Pompadour (Louvre, Paris).

[9] The portrait of Madame Pompadour by François Boucher executed in 1758 (now at Alte Pinakothek, Munich); the portrait of Louis XV was probably that by Jean-Baptiste Van Loo, 1723/1724 (Versailles).

[10] Anthony, early of Shaftesbury, Characteristiks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times (London, 1732), i.144-145. William Hazlitt, The Complete Works of William Hazlitt, ed. P. P. How (London, 1933), xviii.74-75.