Food and drink are recurring themes in the Mozart family letters and in their lives, whether traveling in London, Paris or Italy, at home in Salzburg and, for Mozart, later in Vienna. Leopold was taken with English roast beef and beer and enchanted by Italian fruit. In a letter to his wife, Constanze, dated 8-9 October 1791, Mozart writes, ‘I have just swallowed a delicious slice of sturgeon which Don Primus (who is my faithful valet) has brought me’ and, later in the same letter, ‘I really enjoyed the half of a capon that friend Primus brought back with him.’

But it was not just taste that interested the Mozarts. Food had cultural interest and implications for them as well, including the ways eating habits structured everyday life or its religious implications. It was in part for religious reasons – the differing intersection of food and religion as Leopold practiced it in Salzburg – that French food did not sit well with the Mozarts. Leopold wrote from Paris on 4 March 1764:

- My wife sends her kind regards. She’s disliked the French way of life since the moment we got here; and as for French food, she isn’t at all content. The days of fasting are enough to make you ill since you never see any pastries; here people use four times as much powder in their hair as they do flour, fish is expensive, and since we’ve no servant of our own but have to eat out, we’ve little hope of obtaining anything but dead fish. This is also the cause of our greatest annoyance here. On many fast days we’ve had to eat a meat-based soup, partly because the landlord hasn’t sent us any soup suitable for a fast day, partly because my wife and children can’t eat anything else: here no one’s used to fasting. If one eighth of the population of Paris fasts on a Friday, then I’m not exaggerating; and they can’t even make a proper Lenten soup[1]. I’m not at all scrupulous, as you know, but I still wish that I had some dispensation[2], since I don’t want a guilty conscience, which might place a number of obstacles in my way when it comes to my canonization, since there is otherwise no reason to reproach ourselves, thank God.

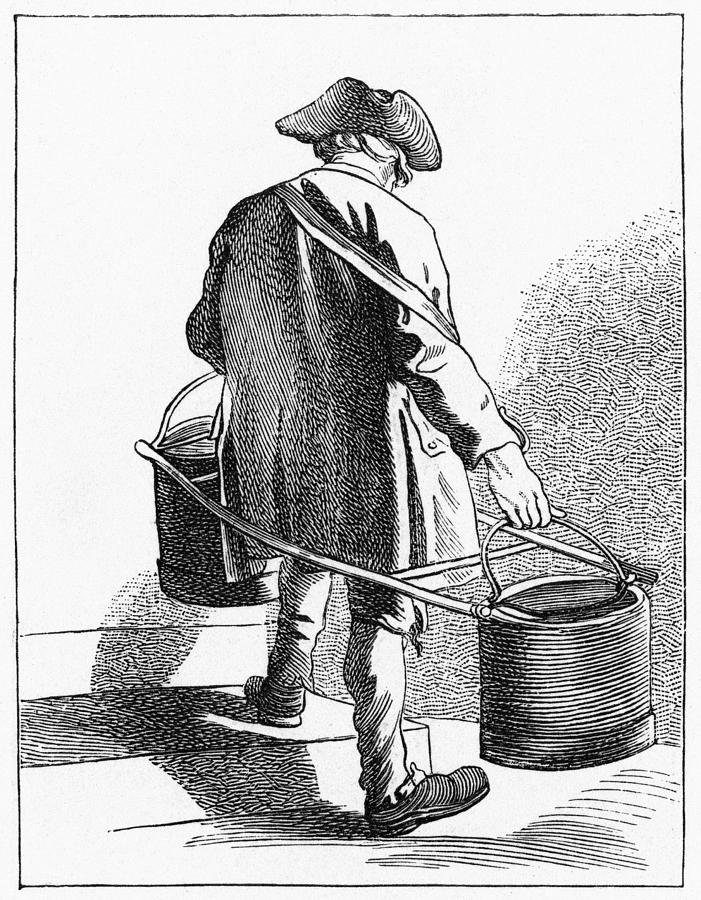

Pierre Angelis, The Fishmonger, 1727 (privately owned)

Paris 1763-1764: Water

Paris 1763-1764: Water

In a letter to Johann Lorenz Hagenauer of 8 December 1763, Leopold Mozart wrote:

- The most disgusting thing here is the drinking water, which is drawn from the Seine |: which looks disgusting :|. There are a few water-carriers who have a royal privilege and who have to pay something to the king, with the result that all water has to be paid for. We have it in the house. They shout out in the street: de l’eau. We boil all our drinking water and then let it stand, which improves it. Practically all foreigners suffer initially from diarrhoea because of the water, each of us got it too, but not too badly.

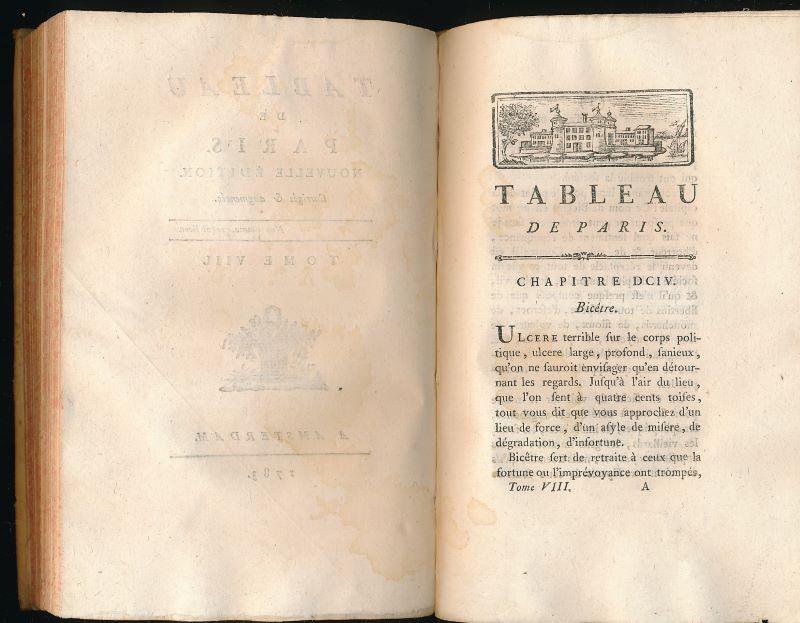

Edmé Bouchardon, Le porteur d’eau, 1737[3]

Unlike London, where pipes were being installed to carry water from the Thames throughout the city, Paris relied on water carriers well into the 1810s. They were monitored by the police and paid the city for the right to fill buckets at public fountains and from the Seine; generally, they received 2 or 3 sous per bucket. A near-contemporaneous account of Parisian water, in Louis-Sébastien Mercier Le Tableau de Paris (Paris, 1781) confirms Leopold’s description, including its deleterious effect on foreigners:

- At Paris, almost all the water that is used is bought. . . The springs are very scarce, and those that remain in so neglected a state that the people are obliged to supply themselves from the river; twenty thousand water carriers, with two buckets on a yoke, go about from morning till night . . . two pails full cost six farthings, or two sous, French money. . . When the river is troubled, you drink muddy water; but what that mud may consist of there is no knowing; however, custom, and the necessity of not being too nice in this case, reconciles the inhabitants to it. The water of the Seine possesses the quality of relaxing the bowels of all who are not in the habit of drinking it; strangers never fail to be attacked by a slight diarrhea; which is prevented by the precaution of adding about a table spoonful of which wine vinegar to each pint of water.[4]

from Louis-Sébastien Mercier Le Tableau de Paris (Paris, 1781)

London 1764-1765: Roast Beef

London 1764-1765: Roast Beef

In a letter from London dated 13 September 1764, Leopold describes English eating habits and diet:

- . . . the ordinary citizen, as I say, arranges his day as follows. In the morning he and his whole family and even the maid drink tea that is incredibly strong and bitter on account of the amount of leaves used. They always add a little milk or cream and eat a lot of sandwiches with it – thinly spread thin slices of bread. Generally you’re also served a few buttered sandwiches which, together with the butter that has been spread on them, have been grilled over the fire. A few hours later the head of the household generally enjoys a good pot of porter [in English in the original] or strong beer [in English in the original], which is strong beer. There are three kinds of beer: porter or strong beer [in English] which is strong; ale [in English], which is what they call light beer; and purl, or wormwood ale. Lunch is at 2 o’clock; this consists either in a large leg of roast mutton or roasted beef [in English], which is English roast beef and known in Germany as rost biff since it sounds almost exactly the same when pronounced in English. To go with it, they eat boiled potatoes or beans that aren’t prepared, but hot melted butter is placed in a small separate dish, allowing everyone to pour as much of it as they like on the potatoes and beans. Or instead of this side-dish they sometimes have a plum pudding [spelled Plumb-pudding by Leopold] as a dessert. This is made of raisins or real apples in a dough. It’s supposed to be a kind of cake but it’s actually pitiful and badly made. It can be obtained from the pastry maker and is eaten cold. Like the Pandurs[5], they also eat onions. In much the same way they enjoy eating lard, not just warm but also congealed. The children and the maidservant drink light beer and are free to go to the casks themselves whenever they like in the course of the day. No one here drinks water; the lord and lady of the house drink strong beer. At around 5 o’clock tea is again drunk with the same ceremonial as in the morning. And at 8 or 9 in the evening the leg of mutton or roast beef from lunchtime is once again set on the table. Now you need to know that on Sundays the mutton or roast beef is served hot. Throughout the week only a small slice is cut from it for each person as long as the meat lasts, and in the evening they also eat bacon fat or cheese or butter, which they spread on the bread and either toast or grill. In a word, they eat like Pandurs. Even people who lead more lavish lives – and there are plenty of them – abide by the same routine as far as tea in the morning and evening is concerned, only they also partake of coffee and chocolate, wine boiled with cinnamon, rose liqueur[6], ice cream etc. and other delicacies.

Anonymous, late eighteenth-century dinner party

Roast beef

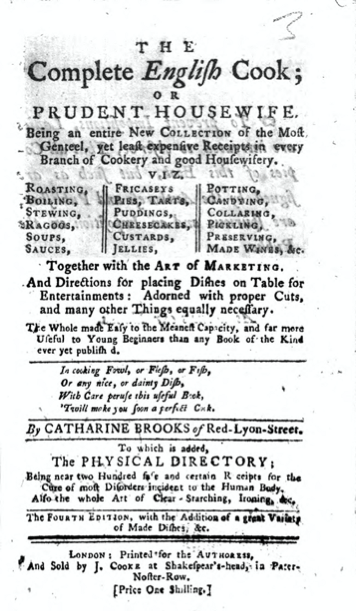

Among the numerous recipes for roast beef published in the eighteenth-century, Catharine Brooks’s from her The Complete English Cook[7] is typical:

- For Roasting Beef.

- If a Surloin or Rump, you must not salt it, but lay it a good Way from the Fire, baste it once or twice with Water and Salt, then with Butter; flour it, and keep basting it with its own Dripping. When the Smoak of it draw to the Fire it is near enough done.

- If the Ribs, sprinkle them with a little Salt Half an Hour before you lay it down; dry and flour it, then butter a Piece of Paper very thin and fasten it on the Beef, put the buttered Side next to the Meat.

- 👉Never salt your roast Beef before you lay it down to the Fire (except the Ribs) for that will draw out the Gravy.

- When you keep it a few Days before you dress it, dry it well with a clean Cloth and flour it all over, then hang it up where the Air may come to it.

Catharine Brooks, THE / Complete English Cook ... London, (1770) : Title page

It is not out of the question that Leopold knew of the cultural importance of roast beef or that he and his family at some time during their stay in London heard the popular patriotic ballad Oh! The Roast Beef of Old England, written by Henry Fielding for his play The Grub-Street Opera and popularized in a setting by Richard Leveridge (1670-1758):[8]

| When mighty Roast Beef was the | Who sully the honours that once | |

| Englishman's food, | shone in fame. | |

| It ennobled our veins and enriched | Oh! the Roast Beef of Old England, | |

| our blood. | And old English Roast Beef! | |

| Our soldiers were brave and our | ||

| courtiers were good | When good Queen Elizabeth sat on | |

| Oh! the Roast Beef of old England, | the throne, | |

| And old English Roast Beef! | Ere coffee, or tea, or such | |

| slip-slops were known, | ||

| But since we have learnt from | The world was in terror if e'er she | |

| all-vapouring France | did frown. | |

| To eat their ragouts as well as | Oh! The Roast Beef of old England, | |

| to dance, | And old English Roast Beef! | |

| We're fed up with nothing but | ||

| vain complaisance | In those days, if Fleets did presume | |

| Oh! the Roast Beef of Old England, | on the Main, | |

| And old English Roast Beef! | They seldom, or never, return'd | |

| back again, | ||

| Our fathers of old were robust, | As witness, the Vaunting Armada | |

| stout, and strong, | of Spain. | |

| And kept open house, with good cheer | Oh! The Roast Beef of Old England, | |

| all day long, | And old English Roast Beef! | |

| Which made their plump tenants | ||

| rejoice in this song— | Oh then we had stomachs to eat and | |

| Oh! The Roast Beef of old England, | to fight | |

| And old English Roast Beef! | And when wrongs were cooking to do | |

| ourselves right. | ||

| But now we are dwindled to, what | But now we're a… I could, but goodnight! | |

| shall I name? | Oh! the Roast Beef of Old England, | |

| A sneaking poor race, half-begotten | And old English Roast Beef! | |

| and tame, |

To listen to Oh! The Roast Beef of Old England, click here:

William Hogarth, The Gate of Calais, engraving 1749

It is less likely that Leopold understood all of its implications, however, for while it explicitly condemns the influence of French taste and fashion in both food and dancing (and is in part a reaction to the derogatory eighteenth-century reference to the English as rosbif by the French), it more generally ridicules Catholicism. At least this was one of the points of William Hogarth’s 1748 painting The Gate of Calais or O, the Roast Beef of Old England (published as a print in 1749; the original is now at the Tate Britain, London): ‘The fisherwomen wearing crucifixes on the left seem to pray to the cheap flat fish in front of them. In the background, through the gate, 'superstitious' locals are kneeling before the Cross, beneath a tavern sign of a dove, symbol of the Holy Ghost, in Hogarth's mockery of the Eucharist. More earthly nourishment, however, comes in the form of the unattainable sirloin of British beef.' (Tate Britain website: to find reference click here.)

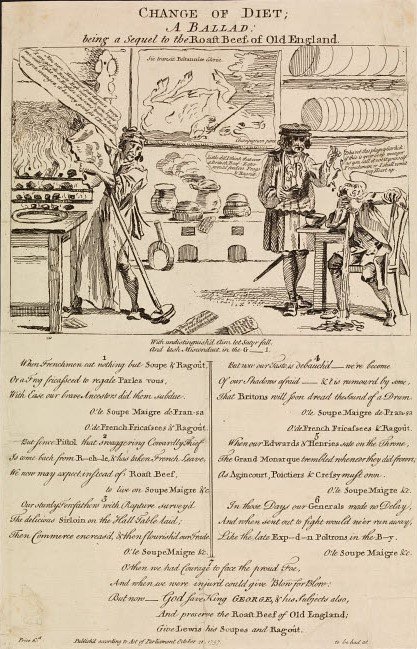

Hogarth’s print gave rise to a further ballad, Change of Diet. A Ballad: being a Sequel to the Roast Beef of Old England, 1757:

Ballad, Change of Diet, 1757 (London, British Museum)

| 1 | 4 | |

| When Frenchmen eat nothing but Soupe & Ragoût, | But now our Taste is debauch’d — we’re become | |

| Or a Frog fricasseed to regale Parlez vous, | Of our Shadows afraid — & ‘t is rumourd by some, | |

| With Ease our brave Ancestors did them subdue. | That Britons will soon dread the Sound of a Drum. | |

| O.’le Soupe Maigre de Fran-sa | O.’le Soupe Maigre de Fran-sa | |

| O.’de French Fricassees & Ragoût. | O’de French Fricassees & Ragoût. | |

| 2 | 5 | |

| But since Pistol that swaggering Cowardly Thief | When our Edwards & Henries sate on the throne, | |

| Is combe back from R-ch-le, & has taken French leave, | The Grand Monarque trembled whnever they did frown; | |

| We now may expect, instead of Roast Beef, | As Agincourt, Poictiers & Cresy must own. | |

| to live on Soupe Maigre &c. | O.’le Soupe Maingre &c, | |

| 3 | 6 | |

| Our sturdy Forefathers with Rapture survey’d | In those Days our Generals made no Delay, | |

| The delicious Sirloin on the Hall Table laid; | And when sent out to fight would ne’er run away, | |

| Then Commerce encreas’d, & the flourish’d our Trade. | Like the late Exp-d-n Poltrons in the B-y. | |

| O.’le Soupe Maigre &c. | O.’le Soupe Maigre &c. | |

7

O’then we had Courage to face the proud Foe,

And when we were injur’d could give Blow for Blow:

But now —God save King GEORGE, & his Subjects also,

And preserve the Roast Beef of Old England;

Give Lewis his Soupes and Ragoût.

Publish’d according Act of Parliament October 21, 1757.

[1] That is, soup without meat.

[2] From fasting.

[3] Further, see Vincent Milliot, ‘Le travail sans le geste. Les représentations iconographiques des petits métiers parisiens (XVIe-XVIIIe s.)’, Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine 41/1 (1994), 5-28

[4] Translation from the English edition of Mercier, published as Paris: Including a Description of the Principal Edifies and Curiosities of that Metropolis (London, 1817), 33.

[5] A Habsburg light infantry unit that first saw duty in 1741 during the War of the Austrian Succession; the term has its origin in Croatian, via Hungarian, and at first referred to guards protecting crops before coming to mean guards more generally.

[6] ‘Rosolie’ in the original. The word ‘rosolio’ for rose liqueur was not commonly used in English until the end of the eighteenth century; see OED Online. March 2020. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/167629?redirectedFrom=rosolio& (accessed March 28, 2020).

[7] Catharine Brooks, THE / Complete English Cook; / OR, / PRUDENT HOUSEWIFE. / Being an entire New COLLECTION of the most Genteel, yet least expensive Receipts in every Branch of Cookery and good Housewifery (fourth edition: London, [1770]), 5-6.

[8] In a letter of 27 November 1764, Leopold explicitly mentions hearing street ballads (even if he found the experience tiresome): ‘Although the poor are generously provided for, there are vast numbers of them; few, however, risk begging in public since this is forbidden; instead, they have a different way of demanding alms, namely, by selling posies of flowers in summer, while others sell toothpicks made from quills, others again sell copper engravings or matches or sewing thread or different-coloured ribbons and so on. Others sing as they pass along the street and sell printed songs, which is the most common method and one that we quickly tired of hearing.’